Tags

Dual Identity, Fatherhood, Language and Identity, Paraguayan American Poet, Poem “Inheritance” by Diego Báez, Poetry Collection Yaguareté White by Diego Báez (USA 2024)

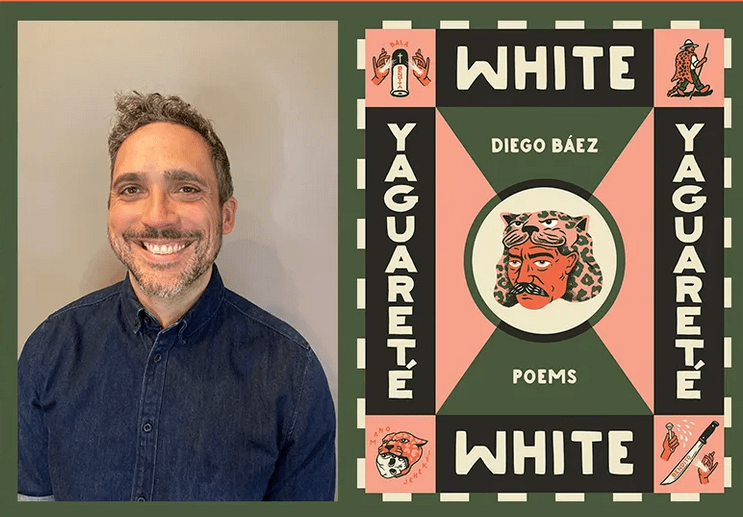

Photo Credit: The University of Arizona Press

My Poetry Corner July 2025 features the poem “Inheritance” from the debut poetry collection Yaguareté White (USA, 2024) by Paraguayan American poet Diego Báez. The collection was the finalist for The Georgia Poetry Prize and a semi-finalist for the Berkshire Prize for Poetry.

Son of a Paraguayan father and a white, Pennsylvanian mother, Báez grew up in Central Illinois in a community devoid of families that resembled his own. His brown skin betrayed his otherness to his classmates. On family visits to Paraguay, his broken Spanish marked him as a gringo. This reminder that he wasn’t quite Paraguayan or American infuses his poetry.

Báez lives in Chicago with his wife and daughter. He teaches poetry, English composition, and first-year seminars at the City Colleges, where he is an Assistant Professor of Multidisciplinary Studies.

Rigoberto González, an American poet, writer, and book critic, notes in his Foreword to Yaguareté White: “Diego Báez [is] the first Paraguayan American poet to publish a book originally in English in the United States.” He adds that Báez is transparent in his debut poetry collection about his struggles understanding his own dual identity. “[H]e didn’t grow up speaking Spanish; and the lack of connection to a Paraguayan community in the United States excludes him from the social and cultural foundations that other South American diasporas provide for their respective immigrant populations and subsequent generations.” His memories of his Paraguayan origin arise from visits to his abuelo’s farm outside the village of Villarrica.

Nevertheless, Paraguay is ever-present throughout the poetry collection in which Báez weaves its colonial history of violent militant whiteness together with its three languages: English, the language of US imperialists; Spanish, the language of the colonizers; and Guaraní, the dialect of the indigenous peoples. In combining the Guaraní word for jaguar, yaguareté, and white in the book’s title, the poet also hints at his dual identity.

In the opening title poem “Yaguareté White,” Báez goes further in linking the indigenous peoples of the Americas. As his Paraguayan father told him when he was a kid, “I was born in America.”

No jaguars wander my father’s village, no panthers

patrol the cane fields caged in bamboo fences,

nestled among the Ybyturuzú, what passes for a mountain

range in Paraguay, the Cordillera Caaguazú. You see,

Spanish adjectives arrive after the noun they describe,

clarifying notes that add color and context.

[…]

And it’s true, no mountain lions roam my mother’s home-

town of Erie, Pennsylvania, wasted city of industry, named for the native

people who once combed it shores, called “Nation du Chat”

by the colonizing French, after the region’s Eastern Panther.

In closing, the poet explains that the jaguar has nothing to do with Guaraní mythology. Rather, Jaguars come to represent / the souls of all the dead. Inseparable from each other, // this people and their origin. So it is, and so am I, / here now in the temple.

Báez tackles the concept of whiteness in his long poem “Basic White” (pp. 72-75), defined in terms of its daily manifestations. The following excerpt are the opening six verses:

basic white is so basic right

basic white is doublespeak for supremacy

basic white enshrines individual liberty

basic white lives for private property

basic white takes what it wants when it wants it

basic white bleeds what it needs to survive

The featured poem, “Inheritance” (pp. 51-53) captured my attention. It’s not often that I come across a poem that exalts the experience of becoming a father for the first time. Moreover, it’s an immediate bond between a father and his baby girl.

While working on his poetry collection, Báez got married and later became a father. During its final publication, his daughter turned three, and then four years. In his interview with Mandana Chaffa for the Chicago Review of Books in February 2024, Báez said: “She’ll be five soon, so the life of the book represents nearly half her own, which is wild. The book closes with two poems for her. It was important for me to include poetic reminders of these moments from early parenthood that seem to last forever but are, indeed, so fleeting.”

The following excerpt, stanzas 1-3 and 7-9, addresses the poet’s need to pass on to his daughter what he has inherited from his Paraguayan father and paternal grandparents.

When my child came into this world,

she didn’t rock mine or turn it upside down

but flipped it insider out. It felt not like a burning fire,

but like a new chamber opening in my heart,

a fourth dimension unbending

between sternum and spine.

Surely it had lived there all along,

huddled with the Spanish

I hadn’t spoken in ages.

[…]

At first, simple whispers suffice:

words for “love” en Guaraní y Español.

How those early endless hours

—then days and weeks—

balloon, uninvited, to encompass the story

I tell myself of her genesis.

The way a point turns to line,

a line to surface, surface to volume,

until all that’s left is time.

In stanzas 12-20, the father imagines his daughter as a young woman, in pursuit of her own dreams, outside the quickly shrinking cage / of a father’s captive heart (stanza 16). The following excerpt are stanzas 12-14 and 17-18:

And I see her already,

moving through timelines I no longer recognize.

An anchor point or past tangent,

I’m already a bystander

in the green blaze of her ascendent arc.

She has changed so much—so much of me—already.

She fills space, and grows, and will not stop

growing, god willing. With hope, Hashem,

she’ll continue to grow

[…]

Because wasn’t it just yesterday

her breath first rounded into syllables,

sílabas into word and words into song?

Was it not just yesterday

she fit inside the makeshift cradle of my arms,

not yet so far removed from this vast world she’d cracked wide open?

The poet’s final two stanzas (21 & 22) bring us back to the present. He closes with an endearing moment that touches my heart.

Of course, all this unfolds in the time it takes to fall asleep,

to sway in the morning sun after a restless night,

her head on my shoulder, something with rhythm on the radio.

I imagine if there’s an afterlife worth living for,

it’s probably this, just like this, forever.

To read the complete featured poem and learn more about the work of Paraguayan American poet Diego Báez, go to my Poetry Corner July 2025.

Wow, thanks for shining a spotlight on talented poet, Diego Báez. What a breathtaking poem. The last lines are deeply touching and heartfelt! 💜

LikeLiked by 2 people

My pleasure, Ada 🙂 I’m so glad that you enjoy the featured poem as much as I did ❤

LikeLiked by 2 people

You’re right.

“it’s probably this, just like this…”

LikeLiked by 3 people

That line also got to me, James ❤

LikeLiked by 3 people

Diego Báez is a very talented poet, Rosaliene. His takes on dual identity, parenthood, and more are interesting and eloquent.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Dave.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So touching, this description of a father and the transformative experience of having a child. It felt like heaven, to me, as well, in that first 24 hours. He also uses a Hebrew word for God: Hashem. I hope his enlarged family anchors him, and that he feels comfortable in that place.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dr. Stein, thanks for sharing your own experience of becoming a father. So glad that you noted his use of the word Hashem. I had to check the meaning. I read somewhere that his wife is Jewish, but I haven’t been able to confirm this.

LikeLiked by 2 people

My understanding is that the word is used as a substitute for the more holy name of God. Only under very special circumstances is the use of the latter permitted. The substitution of Hashem demonstrates reverence and respect.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for sharing this deeper understanding, Dr. Stein.

LikeLiked by 2 people

O, Rosaliene, this post reminds me of how lucky I was to be directed a while ago (doubtlessly via Dave Astor’s literary blog) to your Three Worlds One Vision blog. I don’t think I need to say more to express my admiration for these lines from Diego Báez.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for your kind comments, Dingenom 🙂 I’m so glad that Diego’s work resonates with you ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

A wonderful poet, Diego Baez puts into words what many of us feel, but can not express, as we watch our children grow from birth to adulthood. You think you know love and then you have a child and you realize love is boundless. Happy Sunday Rosaliene. Allan

LikeLiked by 2 people

Allan, I’m so glad that Diego’s featured poem speaks to your own experience as a father. What a gift to fathers everywhere ❤

LikeLiked by 2 people

I enjoyed reading the full poem and your profile of this poet, Rosaliene. Reading about Báez made me think that there are so many ways we can feel like outsiders, though systemic barriers make that feeling so much more acute. It is wonderful how, despite societally imposed norms, he blossoms with love for his daughter that lifts his spirit. The ending is indeed an endearing moment. Thank you for highlighting this writer.

LikeLiked by 2 people

My pleasure, Steve. All is not bleak in his collection. In several poems, he also honors his paternal and maternal grandparents for their positive influence in his life.

LikeLiked by 2 people

He does seem an honouring fellow, and I did pick up on the more positive aspects on his writing… certainly the parental love and devotion.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I like his way with words. He’s smart and talented.

LikeLiked by 2 people

He is, indeed, Neil. So glad that you appreciate his work 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Awh, man. That must have been rough having a sense of not belonging anywhere. Poor child. Glad he’s okay now. It’s nice how so many people can turn to poetry to help them work through their emotions and challenges.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So true, Ilsa. It’s tough to take in when we’re young. He’s definitely in a better place today.

LikeLiked by 2 people

His work so well explores the problems of such mixed heritage yet having experiences, like parenthood, common to us all. I am reminded of my so stable background going back centuries, yet also aware that there are other aspects to life that I could never have.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So true, Derrick. Regardless of our origins, we do have a lot in common as humans.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Quite so

LikeLiked by 2 people

Beautiful imagery. A soul laid bare. xo

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Pam. So true ❤

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for sharing, Rosaliene. I enjoy reading about the poets’ backgrounds and journeys as much as the stellar poetry you bring us. 👏🏻

LikeLiked by 2 people

My pleasure, Michele. I’m so glad that you appreciate my approach to sharing the work of the amazing poets among us.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I look forward to your shares. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 2 people

🙂 ❤

LikeLiked by 2 people

Diego Baez’s beautiful insights about the love of a parent for a child seem to transcend race and nationality. Thank you for this window to his soul and his experience.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It sure does, JoAnna. It’s part of our shared humanity.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Stunning visuals and a deeply honest expression of the soul.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for sharing your thoughts, Ravindre.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks a lot for sharing this fabulous poem!!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

My pleasure, Luisa 🙂 ❤

LikeLiked by 2 people

🙏🌹🙏

LikeLiked by 2 people

Excellent poem 💝

Thanks for sharing 🌷🏵️

Grettings from 🇪🇦🌈🌞

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much for dropping by 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rosaliene, I can see why those lines would capture your heart, they’re sublime in the way they capture a parent’s rapture with their child! Love his poetry!

LikeLiked by 2 people

So glad that you also love his poetry, Tamara 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, it’s quite lovely! 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for sharing another great poet, Rosaliene. His words about “basic white” are so right. I like his reference to the mountain lion because my parents live in a place in Pennsylvania where the mascot is the mountain lion and sadly, the mountain lions are long gone.

LikeLiked by 2 people

My pleasure, Mara. Isn’t it sad about the mountain lion? The same is true for the California grizzly bear, featured on our state flag. They, too, have all been killed following the Gold Rush.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So tragic.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It is, indeed, Mara 😦

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for introducing us to the fabulous writer, Báez, Rosaliene. I found it interesting that he resides in Chicago. I’m fascinated about where people come from and what shaped the life they live. Báez certainly is captivating.

LikeLiked by 2 people

My pleasure, Mary. So glad that you find him captivating. I’ve observed that Americans move about a lot across states, especially for higher education and job opportunities. Several of my neighbors have moved here from other states, one as far away as Virginia.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Oh wow Rosaliene, Diego Báez is an intriguing poet. The poems you featured are so spot on. I love his explanation about the representation of the jaguar. He is deeply insightful and I can understand how and why you were so captivated through your spotlight on his work. Thank you for introducing him to your audience sis. 😊🙏🏼🤗💖😍

LikeLiked by 3 people

My pleasure, Kym. I’m so glad that you like his work 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Oh yes I did Rosaliene. I love the interesting spotlights you share with us that are new to me. I appreciate that and I am sure they do too! 🥰💖😍

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s great, sis!

LikeLiked by 1 person

🥰💖😘🙏🏼😊

LikeLiked by 1 person