Tags

Climate Crisis, Earth Day 2025: Our Power Our Planet, Hurricane Maria/Puerto Rico 2017, Poem “Ricantations” by Loretta Collins Klobah, Poetry Collection Ricantations by Loretta Collins Klobah, Puerto Rican Poet

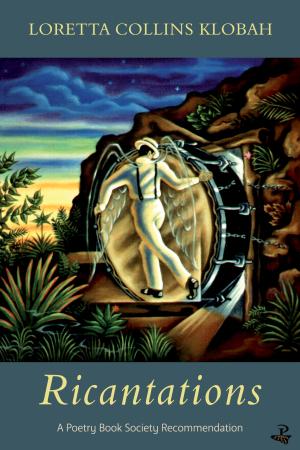

Puerto Rican Poet Loretta Collins Klobah / Oil Painting on Front Cover: Ángel Plenero by Samuel Lind

Photo Credit: Peepal Tree Press (UK, 2018)

My Poetry Corner April 2025 features the title poem from the poetry collection Ricantations (Peepal Tree Press, 2018) by Puerto Rican poet Loretta Collins Klobah. Born in Merced, California, she earned an M.F.A. in poetry writing from the Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa, where she also completed a doctoral degree in English, with an emphasis on Caribbean literary and cultural studies. She spent four of the nine years of her doctoral study in Jamaica (Caribbean) and West Indian neighborhoods of Toronto (Canada) and London (UK). Since the late 1990s, she lives in San Juan, Puerto Rico, where she is a professor of Caribbean literature and creative writing at the University of Puerto Rico.

Growing up in an English and Spanish working-class household has influenced Klobah’s style of blending Spanish and English in her work. Her mother had Spanish and Scottish heritage, her father Cherokee and Irish. Her Mexican American godparents taught her Spanish, widely spoken in Merced where she grew up. The title of her collection Ricantations appears to be a blend of these two languages.

Klobah began writing poetry in primary school as a way of processing life and engaging with the world. At eighteen years, on becoming part of the active poetry community in Fresno, California, she began receiving serious mentoring from former US Poet Laureate Philip Levine and other award-winning poets.

“I don’t write love poetry, and I don’t rhyme,” Klobah told Trinidadian poet Andre Bagoo during a 2012 interview for the Caribbean Beat magazine, following the release of her award-winning debut poetry collection. “I write because I want to communicate with readers in a way that matters, makes an impact, or makes some kind of beneficial difference in the reader’s thoughts and in the society.”

Klobah’s second collection of poems in Ricantations portrays the harsh realities of life in Puerto Rico’s colonized society, ransacked by debt, mass migrations, narcoculture, gender violence, and hurricanes. The featured title poem describes the poet’s shared trauma of surviving Hurricane Maria that struck the Caribbean island on September 20, 2017. The strongest storm to impact the island in nearly ninety years, Maria caused a major humanitarian crisis for survivors. It not only flattened neighborhoods but also destroyed the island’s power grid and telecommunications network. An estimated 2,982 people lost their lives.

“The entire island looked like an atomic bomb had been dropped on it,” Klobah told Vahni Capildeo during their 2018 interview for PN Review 242. “When I first was able to get out of my house and into the streets, my thought was that this island can never recover from this destruction.”

Klobah’s description of Hurricane Maria and its aftermath is surreal, at times hallucinatory. In the first five stanzas of her long narrative poem, she also bears witness to the storm’s assault on non-human life (p. 99):

Hurricane Maria wheeled over the sea,

a day away from upending and crushing cars,

prying roofs, plucking up electrical poles,

cracking trees to the stub,

flooding plantain fields of Yabucoa.

Our avocado trees, roots rumbling,

threw down their green pears all at once,

so that when they were broken and uptorn,

their stones would tap into soil.

[Yabucoa is a town and municipality in the southeastern region of Puerto Rico.]

In the fourth stanza (p. 99), peeping through the poet’s louvred bedroom window, we see an enormous old iguana, 5 or 6 feet / from nose to tail. He sat at the top corner / of my vine-covered fence, / bowing down chain-link with his weight. // In his heavy-lidded / green eyes, what knowledge? I was in the cabin / of a ship, and he was both captain and figurehead, / an ancient dragon sailing us into a sky bomb.

The aftermath of Boombox Maria unreels in stanzas six to thirteen (pp. 100-101):

When neighbors cleared trees and debris,

we went out onto the swamped streets.

Ceiba trees’ massive trunks pulled up like radishes.

Piñones erased by sand, beach huts gone.

Signs and stop-lights curled wreckage –

Cemetery wall strewn along the hotel strip.

Young iguanas, ousted from shorn treetops,

ran into the road and were run over.

Honey bees flew into our homes,

their hives and colonies carried away,

surviving plants disrobed of flowers and fruit.

Bats whisked overhead at twilight.

Without shelter, families slept on sodden couches, / in bathrooms, on patios, in leaking garages. Without available medical assistance, the poet allowed her diabetic daughter to evacuate the island. Her own ulcerated legs dripped sap and pus. With three neighbors, she traded food, solar lights, and small bags of ice. / We bathed in bowls and hand-washed clothes / with tainted water contaminated with animal carcasses and sewage.

“Neighbors got to know each other because we all needed mutual help,” Klobah told Vahni Capildeo. “To some degree, islands helped each other out. However, the aid response of the colonial countries that gained their wealth through using our islands as slave plantations, and still benefit from captive markets and disaster capitalism, was far from adequate. This necessary aid and infrastructural strengthening should be considered an ethical imperative and a form of reparations.”

In the closing two stanzas (14 and 15), Klobah reflects on lessons learned from their shared trauma (p. 101):

Nothing now is normal

though remaining trees rush to green up

and flower, dogs bark, and the sea still

waves its bacterial flag over the shores.

I hear quarrelling macaws and parakeets.

Ay Le Lo Lai songs move us,

but not to full tenderness.

Still, we feel new incantations of something

primal in us, allied by our hurricane grief,

disordered, but sentient of how we are related, neighbors,

iguanas, honey bees, bats, birds, trees, islands.

What is possible now? Can we do some things

differently now?

Over seven years have passed since Hurricane Maria pulverized America’s Caribbean Island territory of Puerto Rico. Our climate change-denial president who sought to withhold about US$20 billion in federal hurricane relief funds for the island is, once again, at the helm. The questions posed in the ending of “Ricantations” are a call to action. “Writers, if not politicians, need to imagine and voice the substantial changes that we urgently need to make,” Klobah told Vahni Capildeo.

With its theme Our Power, Our Planet on Earth Day 2025, observed on April 22nd, the emphasis is on people power as the driving force behind the global transition to renewal energy sources. According to their release: “It’s the collective voice of concerned citizens that pushes governments and corporations to make bold commitments and take decisive action.” Join me in responding to their call to “embrace a powerful, renewable future. It’s Our Power, it’s Our Planet.”

To read an excerpt (stanzas 1, 4, 7, 9, 14 & 15) of the featured poem “Ricantations” and learn more about the work of Puerto Rican poet Loretta Collins Klobah, go to my Poetry Corner April 2025.

Thanks for sharing this wonderful poetry. “allied by our hurricane grief” is so moving. I can understand how this shared trauma brought people together, which is affirming. 💜

LikeLiked by 3 people

My pleasure, Ada. Shared trauma has a way of breaking down barriers between people.

LikeLike

A great introduction to a great poet, Rosaliene! Loretta Collins Klobah’s poetic words about Hurricane Maria and its aftermath are devastating and moving.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Dave. So glad that her poetry moves you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

An important, more than essential message from the poet. Does the average American even know what happened? Does he care? Might the poet offer a charity to which we can help our brothers and sisters rebuild? Thank you, Rosaliene.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dr. Stein, Klobah’s comments regarding her poem “Ricantations” were made in 2018. I’m not aware of any charitable organizations still active in collecting funds for Puerto Rico. According to a case study by Kate Johnston, Princeton University, published March 2024, full recovery has been hindered by the complexities of receiving allocated FEMA disaster recovery funds.

You can read the case study at the following link:

STRENGTHENING TRUST AND CAPACITY: REBUILDING PUERTO RICO AFTER HURRICANE MARIA, 2017 –2023

Case Study by Kate Johnston, Princeton University, published March 2024

https://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/publications/strengthening-trust-and-capacity-rebuilding-puerto-rico-after-hurricane-maria-2017

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Rosaliene .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful vivid pictures of destruction caused by climate disasters, both external and internal. Who can deny that climate change is here, no matter how caused or no matter how some think it is cyclical. Stop denying and start allying. Happy Sunday Rosaliene. Allan

LikeLiked by 2 people

Allan, thanks for sharing your thoughts. The cause does matter. How does one find a solution without determining the source of the problem?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I like the way she writes. And, as we know, Trump’s response to that hurricane was pathetic.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Neil, I’m glad that you like Klobah’s poetic style. I still remember him throwing paper towels to the crowd during his visit.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very beautiful text, Rosaliene, and at the same time disturbing when we simultaneously remove the topics of climate, environmental protection, etc. from the menu. This approach reminds me of little children who cover their eyes and then think no one sees them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Friedrich. Our predicament is, indeed, disturbing.

LikeLike

Love this part: “I write because I want to communicate with readers in a way that matters, makes an impact, or makes some kind of beneficial difference in the reader’s thoughts and in the society.”

And I’m glad she found this outlet early in life and was mentored later by a master. Good on her!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Ilsa, I always find what motivates writers of special interest. It’s also important to acknowledge the people who have helped us to achieve our dreams.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love her portrayal of the old iguana as captain of the ship / island. She illustrates well how horrible these disasters are for the people and land long after the storm has passed and the media has forgotten them. But also, how these disasters can bring people and land closer together, something I hope we can all do as we’re really all on the same island if you think about it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mara, I was also struck by her portrayal of the old iguana. You’re so right in noting that we’re really all on the same island. We’re all trapped on this planet called Earth. Our political borders are meaningless in the face of Earth’s operational systems.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So sad that we’re using the word “trapped” to describe our existence on a planet that could be, if we all worked together instead of against each other, a wonderful world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So sad and true, Mara 😦

LikeLiked by 1 person

An impressive resume and interesting personal background. I am inspired by why she writes. It is evident that she is accomplishing that! Thank you for sharing, Rosaliene. 🙏🏻

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure, Michele 🙂 I also find it telling that she did not abandon the island following the disaster.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I loved this share of Puerto Rican poet Loretta Collins Klobah and her vivid unshakable poetry, Rosaliene. Her method of delivery is so appealing. Brilliantly realistic simplicity! 💗

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Cindy 🙂 I’m so glad that you like her poetic vision.

LikeLike

Oh my gosh Rosaliene, I love this spotlight and review of Loretta Collins Klobah’s work. Thank you so much for introducing us to a lovely poet. I appreciate her cultural contributions and yours sistah friend. What a visionary! Hugs and smooches!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kym, I’m so glad that you love my selection this month. Hugs, sistah 🙂 ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are so very welcome Rosaliene. 🙏🏼 Your attention to detail is poetically infectious! Much love sistah girlfriend! 🥰💖😘

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Kym! ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re so very welcome my friend. 🤗💖😍

LikeLiked by 1 person

I appreciate how she includes the grief and trauma of non human life- expanding our circle of compassion. We are all related.

LikeLiked by 1 person

JoAnna, her inclusion of the trauma of non-human life also captured my attention. We humans often forget the impact these extreme weather events also have on other lifeforms on which we depend for our survival.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ricantations is a very moving work. Thank you for introducing me to the poetry of this important Puerto Rican writer. The devastating effects of colonialism and the most recent severe hurricane are so evident still today, as witnessed in our December visit to the island.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rebecca, I’m glad that you’ve been moved by Klobah’s poem. I thought of your recent visit to Puerto Rico when researching Hurricane Maria. As you’ve witnessed, their recovery is still ongoing. I’ve learned that obtaining approved FEMA disaster relief funds is a highly complex process.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for again shedding a bright light on an important and powerful voice for the voiceless, Rosaliene. The poets you feature are always so invested and activated in the fight for the greater good.

I recall seeing news footage around the time of Maria with all the devastation, and dear friends have family in Puerto Rico so we felt a connection, of sorts, not that that should matter for empathy’s sake. I also remember the paper towel president making much ado about his appearance there. I admit I don’t truly understand Puerto Rico’s relationship to the US but it seems it’s a territory which should afford it the full might of the resources available at the hands of those in DC yet it seemed utterly neglected.

I apologize that I’ve missed so many of your posts, due to taking on a pretty much full time role in our recent election. It felt like really important work I needed to do, and was a very good experience though I’m glad its intensity has passed so I can resume reading the blogs I follow.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Steve, thanks for catching up on my posts and sharing your thoughts. I read about your involvement in the recent elections in one of your blog posts. Really important work, indeed. Sad to say, the US-Puerto Rico relationship remains exploitative.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s so sad the country isn’t embraced and supported.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is, indeed, Steve. While they are American citizens, Puerto Ricans who live on the island can’t vote in federal elections. As such, they have no representative in the Senate or House to fight for their needs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sadly, that doesn’t seem likely to change.

LikeLiked by 1 person