Tags

Brazilian Poet Rubens Jardim, Poema “Expropriation / Expropriação” by Rubens Jardim, Poetic Catechesis / Catequese Poética Movement, Poetry Collection Outside of the Bookshelf / Fora da Estante (2012) by Rubens Jardim, São Paulo/Brazil

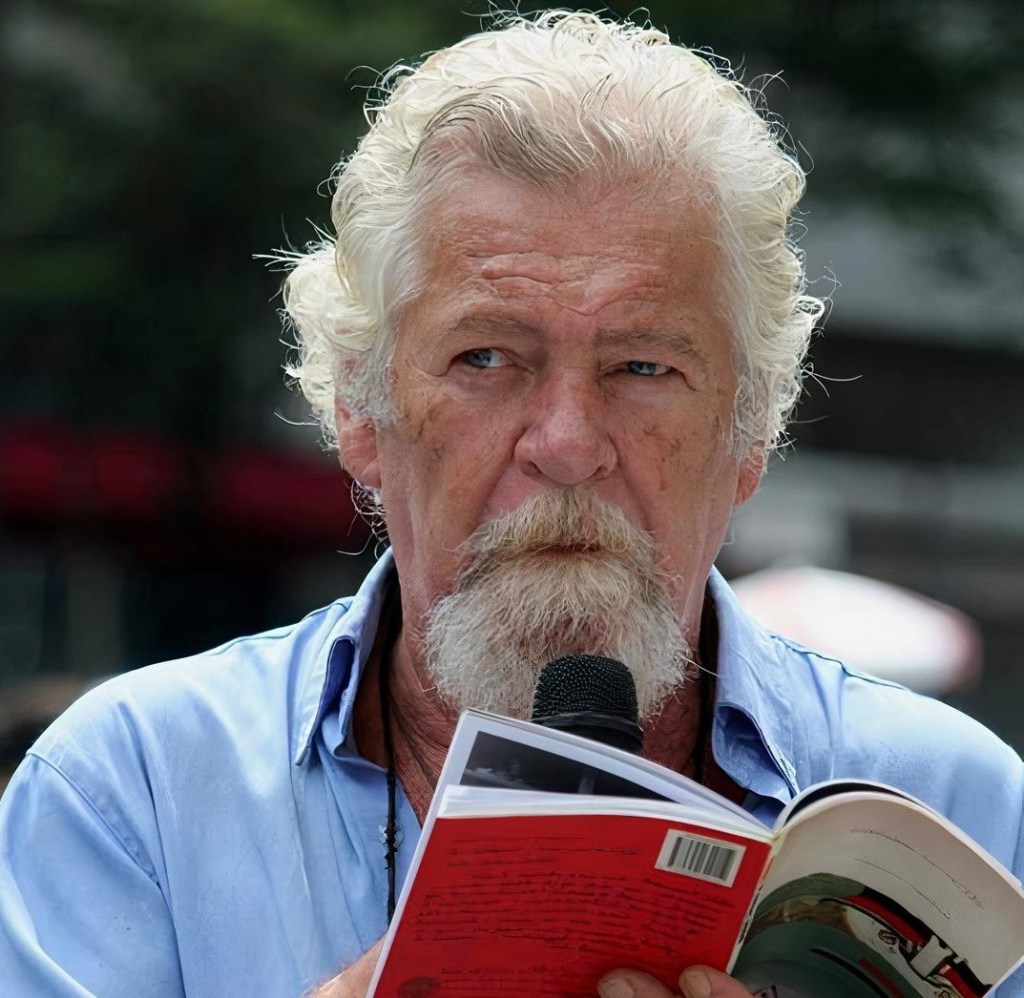

Photo Credit: Brazilian Editora Arribaçã

My Poetry Corner March 2025 features the poem “Expropriation / Expropriação” from the poetry collection Outside of the Bookshelf / Fora da Estante by Brazilian poet and journalist Rubens Jardim (1946-2024). Born in Vila Itambé in the interior of São Paulo, he was one of three siblings, with an older brother and younger sister. Poetry was always a part of his life. An aunt, passionate about poetry with a magnificent collection, would always recite Brazil’s renowned poets at family gatherings. He attributed his skill at public poetry readings to her.

In an interview with Revista Arte Brasileira, following the publication of his Anthology of Unpublished Poems / Antologia de Inéditos in 2018, he spoke a lot about poetry and its importance in his life.

“Poetry for me is alchemy. It is the transformation of the ignoble into the noble, of the invisible into the visible, of the unspeakable into utterance….

I believe that true poetry increases humanity in man. It shows that if there is a flower, there is also hunger…. Furthermore, poetry is a constant struggle against alienation. It’s nonconformity. Indignation…. What’s more, poetry does not bend to anything. Averse to classification and closed thinking to transformation, poetry does not tolerate dictatorship—not even dictatorship of the word…. It’s also a way of living. It’s an attitude towards and within life. And if I continue writing poems—even knowing that poetry is useless—as the poet Manoel de Barros enlighteningly said—it’s because I like to believe that, thanks to poetry, I have kept the flame of hope for transformation alive.

The title of the featured poem “Expropriation” is not a word commonly used in English. More common words used include eviction, foreclosure, disinherited, and disowned. There’s also the word dispossessed mostly used, I think, within religious and social justice circles.

When Jardim published this poem in his collection Outside of the Bookshelf in 2012, the world was still recovering from the 2008 global financial crisis, originating in the US housing market, when millions of people lost their jobs and homes. Foreclosure became a common and dreaded word.

Jardim’s poem, divided into three stanzas of unequal length, is very sparse. Nevertheless, it addresses a society that disowns those among us who are considered outsiders.

1

When I was little

and walked hand in hand with my mother

the whole world was my home.

Today, not even my home

is my home.

Born in 1946, after the end of World War II, the poet grew up in the 1950s during more stable times. His childhood in Vila Itambé was idyllic. Everything changed drastically in the 1960s. He was eighteen years old when, on April 1, 1964, the military staged a coup, plunging Brazil into a military dictatorship for the next twenty-one years. It was the turning point in his life as a poet. The teenage poet joined the Poetic Catechesis movement started by Brazilian poet Lindolf Bell (1938-1998) shortly after the coup.

As Jardim said during his 2018 interview with Revista Arte Brasileira:

“The aim of this movement was to bring the poet closer to the people. That’s why we held public poetry readings in squares, colleges, schools, bars, libraries, nightclubs, theaters, unions, clubs, and bookstores. As a result, Poetic Catechesis became very well-known and even featured in the media. We traveled a lot around the interior of São Paulo and other states in Brazil.”

As was expected, the movement faced pushback from the military regime. In talking about this period of his life in his book Proesia and Other Poetic and Proethical Questions / Proesia e Outras Questões Poéticas & Proéticas, published in May 2019, Jardim relates that they faced bayonets, tear gas, explicit intimidation, and censure, but refused to be silent. Instead, “these poets testified and denounced, with absolute legitimacy, all the stain on one’s reputation and all the horrors of that period” (pp. 34-35).

2

The angels have disappeared

from the mirror.

From the street.

From the villa.

They no longer live

not even in the churches.

The poet describes so well what we now face here in the United States. The teachings of Jesus to love our neighbor as we love ourselves are considered “woke”—detested and criminalized. We are kidnapping our immigrant neighbors and deporting them to a maximum-security prison in El Salvador…without due process. Unhappy the innocent young man trapped in this nightmare.

In the aforementioned book (2019), the then 73-year-old poet writes (p. 24):

“Life is, today, compulsive, superficial, ugly, obscene. You are either inside or outside. Except that, no one knows anymore how to distinguish what is inside and what is outside. The limits and borders were exposed, exceeded, desecrated. We are all—one way or another—empty balloons, virgin film, blank paper—where we are being registered for what one should dream, what one should want, what one should have. Or how one should be….”

3

Before, the world was a gift

refuge

offering.

Today I am outside of everything.

Always outside.

Always in the face of things

in the face of the world

in the face of men.

Alone before God.

As a Caribbean immigrant who has adopted the United States as my home over the past twenty-one years, I, too, am outside of everything. Unless I possess billions of dollars to buy my way into the ruling class, I am worthless. My contribution to society means little. I have no rights of free speech, as provided under the constitution. I am disinherited. I am disowned. I am expropriated.

To read the complete featured poem “Expropriation / Expropriação” in its original Portuguese, and to learn more about the work of Rubens Jardim, go to my Poetry Corner March 2025.

So very topical. When I read the title I thought the poem must have just been written. Nothing much changes it seems

LikeLiked by 4 people

So sadly true, Derrick 😦 Things just seem to get worse over time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

He was a deep thinker, as this shows: “ . . . I like to believe that, thanks to poetry, I have kept the flame of hope for transformation alive.”

LikeLiked by 3 people

Neil, I got the same impression when reading his responses during interviews.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such an insightful and interesting post. “Poetry is alchemy” is an intriguing insight into his unique creative process. Thanks for sharing! 😊🌸

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Ada. It’s always a joy to share the work of great poets 🙂

LikeLike

And it has always been thus, the cycle of enlightenment to hatred. What a poet for the times, if only the politicians would read more than just their manifesto. Fascism can happen anywhere. Have a good Sunday Rosaliene. Allan

LikeLiked by 2 people

So true about fascism, Allan. Worse still, when we the people in Western democracies believe that it can’t happen to us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Powerful post, Rosaliene. Rubens Jardim and his poetry are impressive, and, as you note, what he and others went through in Brazil (and elsewhere) is unfortunately very relevant to what is happening in the U.S. today. 😦

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Dave. Over more than a decade of featuring Brazilian poets, I was surprised to come upon his name during my search at such an opportune moment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So few words in his verses, but yet it is very powerful. I appreciate your thorough interpretation and context to help better understand his meaning. Maggie

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Maggie. I’ve found that interviews are always great ways of understanding a poet’s influences and belief system.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is really powerful poetry! I might not have had Jardim’s experiences but the quotations you make resonate with me. That first verse “When I was little…..not even my home is my home”. Goodness, that is just how I have felt for many years. Thank you, Rosaliene, for introducing us to this poet. 🤗😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure, Ashley 🙂 I’m so glad that Jardim’s featured poem resonates with you as it did for me. “Home” reaches far beyond the confines of the personal spaces we occupy as citizens. When our society undergoes a transformation–for good or for bad, mostly bad–our sense of belonging is also transformed. Jardim not only perceived the growing alienation, but was also able to express this in words that we the people can understand. He was, indeed, a poet of the people and for the people.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rosaliene, I even mentioned this poem & your reference to it in my comments on Friedrich Zettl’s latest post! 🤗

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the mention, Ashley 🙂 Friedrich’s latest post also reflects a growing depression we the people of Earth also face during these chaotic times.

LikeLiked by 1 person

His poem has significance in today’s events. Powerful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Tamara. It does, indeed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“I am worthless. My contribution to society means little. I have no rights of free speech, as provided under the constitution. I am disinherited. I am disowned. I am expropriated.”

Yes. Most of us are.

Rubens Jardim’s poetry is beautifully concise and says much of what I feel so very well. Thank you for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure in sharing, Ginger. I’m so glad that his poem resonated with you, too. I believe that this widespread feeling of alienation has driven us into the arms of an authoritarian leader who has promised to relieve us of all our woes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rosaliene, thank you for this excellent article about Rubens Jardim, and for translating his work. He seems like he would have been a wise and thoughtful man.

I like the way you splice the three parts of the poem with your own narrative. This effect adds to the drama of the piece and underscores the reasons he wrote his poems.

It is disheartening to know that past battles for basic human rights and decency continue to be re-fought around the world. Your last paragraph is like a gut punch emphasizing that brutal situation. I am sorry that you’re having to endure such times as you are.

LikeLiked by 2 people

PS: I enjoyed reading more about Jardim on your Poetry Corner.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Steve. Much appreciated 🙂 ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure, Steve. Thanks very much for your kind comments. Rubens Jardim, in my estimation, was a wise and thoughtful man. His legacy, through his poetry collections and other important literary publications, lives on after his passing.

I appreciate your supportive remarks regarding the chaotic world we now live in that also extends across our borders into Canada (your home) and Mexico.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re very welcome, Rosaliene. May we find a way to endure this chaos and turn it into something good for all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amen to that, Steve.

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙏🏼

LikeLiked by 1 person

PS: on your other site you refer to Jardim’s official site not being available. Have you tried searching on the Wayback Machine (a project of the Internet Archive)? I’ve used it successfully to find archives of web pages that are no longer active.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for this info, Steve. I’ve never used the Wayback Machine. A search just revealed that his website has been deactivated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s too bad. Sometimes it will find pages that were archived years ago. I forget the best way to use it for that purpose, but it is often possible. Did your search give you a banner with different time points? If not, then there are probably no archives retained anywhere.

LikeLike

Steve, I will keep your pointers in mind for future searches. Thanks again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Whenever you share a poet and their work, I find myself wishing I were a poet, especially after reading Jardim’s quote from the 2018 interview. So much power there. I appreciate you bringing these poets into our lives, Rosaliene, and including your own insights and experiences. I wish I could protect you and your sons, and everyone else from this horrific cruelty. Thank you for being a light in this world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tracy, we’ve have all been blessed with different gifts to share with the world. Therein lies our power.

I’m glad that you appreciate my monthly Poetry Corner 🙂 I give thanks to my dear friend and poet, Angela Consolo Mankewicz (1944-2017), who opened my vision to the power of poetry.

LikeLike

You’re very wise, Rosaliene. If we were all poets in this world, we’d miss out on other contributions. I add my thanks to yours for the guidance of your friend/poet, Angela. Her gift keeps on giving.

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙂 ❤

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing Rubens Jardim with us, Rosaliene. His poetry is an awakening we all need to experience before we can and will act. The world should be a gift for all of us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure, Mara. Sad to say, I cannot think of a time when the vast riches of the world were a gift to be (equally) shared among the masses of humanity. Thank the gods that we have no control over the Sun that gives life to our planet!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank the gods for that although I wouldn’t put it past some of our current rulers to try.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a poignant way to look at what is happening in the world and I can’t say I disagree, given how this current administration is making this country look very different from the one I have called home all these years. It rocks one’s very soul, sadly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Pam. We’ve lost our way 😦

LikeLiked by 1 person

😳😔

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rosaliene, oh my goodness, thank you for sharing this powerful spotlight on Rubens Jardim. 🙏🏼 I was not familiar with him or his work. Now, this stanza is so very relative:

When I was little

and walked hand in hand with my mother

the whole world was my home.

Today, not even my home

is my home.

What an awesome share! 🥰💖🙌🏼

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Kym. I’m so glad that you connected with his featured poem. Finding him was serendipitous.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh yes indeed Rosaliene. How awesome! 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Compelling poetry. Thank you for sharing, Rosaliene. I enjoyed reading about his aunt’s influence.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure, Michele. How many of us grow up with an aunt who loves and recites poetry at family gatherings?

LikeLike

“I am worthless. My contribution to society means little. I have no rights of free speech, as provided under the constitution. I am disinherited. I am disowned. I am expropriated.”

It made me very sad that you feel this. In God’s Kingdom and truth, this is a lie. You are an importance daughter of the King and you will share the inheritance of Jesus.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dawn, it is not of the Kingdom of God that I speak. Rather, I speak about the upside-down world in which I now reside.

LikeLiked by 1 person

❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

“The angels have disappeared from the mirror…… the angels no longer live not even in the churches”. The 2nd stanza confirms what’s written in the Bible that this period is marked by an increase in wickedness, deception and rebellion against God. There’s Moral decay and Lawlessness.

Talking about deception, it reminds me of the recent outrageous deception by handful white individuals that Black South Africans are causing white genocide, the nerve!

May the soul of the author rest in peace!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Zet Ar, thanks for sharing your thoughts. The moral decay and lawlessness are now being promoted as acceptable norms for our society. Empathy is a weakness, according to the world’s richest man. That should not be a surprise, considering that he was born of apartheid in South Africa. Jesus weeps.

I am saddened to learn about the latest developments in your country. It would appear that, like me, you also live in an upside-down world. Our beloved Nelson Mandela weeps.

LikeLiked by 1 person

True, apartheid is in his DNA. Now birds of the same feathers flock together! People tend to forget that God humbles the proud including those who make themselves gods of this world!

As for my country men and women, they will be strong and survive!

LikeLiked by 1 person

❤

LikeLike

To be outside of everything. One begins to feel this way even while the days pass without notice, unless one wishes to notice or can’t help it. Much of our country assumed that “it can’t happen here.” “Here” is becoming the same as “over there.” You and Jardim always knew. A dreadful knowledge.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dr. Stein, your comments brought me to tears. To know what lies ahead is, indeed “dreadful knowledge” since one is powerless to effect meaningful change. I keep moving forward by preparing myself, in every way possible, for the deepening national and global crises that are unfolding in real time while we continue to treat each other as the enemy.

LikeLike

Many are with you, Rosaliene. Don’t give up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The struggle continues, Dr. Stein. Thanks for your friendship and support ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

The poet, his explanation, and your comments are insightful, Rosaliene. There is so much here, I have to return and read it again. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Mary.

LikeLiked by 1 person

When I read, “I am worthless. My contribution to society means little. I have no rights of free speech, as provided under the constitution. I am disinherited. I am disowned. I am expropriated.” I think, NO! This is not true! Wait, does Rosaliene feel this way? I do not want to discount your feelings. I just don’t want it to be true. I know you are not worthless. You are a valued member of your community and here on WP. But I must accept and honor your feelings and imagine how I would feel…. Even with my undeserved privilege, things in the US are scarier than I want to admit. So much despair. Thank you for sharing this truth. I’m hoping we will survive and eventually heal, but now we are in the midst of frightening turmoil. I believe the angels are still here, somewhere, but they are crying. Maybe poets like Rubens Jardim, and poetry that does not tolerate dictatorship, will help us get through. Thank you for bringing him to us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

JoAnna, this is not what I believe about myself. Rather, this is the way I am being treated/regarded under the anti-immigrant policies at play across our country. I will address this more fully in my next weekly post. I also believe that angels walk among us, giving us the strength to overcome the dark forces.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for clarifying. Sometimes I am too literal in my understanding. I look forward to your next post and love what you wrote about angels among us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

JoAnna, I was happy to clarify my meaning. As part of the body politic, we are impacted at different levels by local and national policies that govern our lives.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m very sorry you are being regarded this way by the current anti-immigration policies here. I can see that. They have no clue about the importance of diversity and the value of each individual.

LikeLiked by 1 person

JoAnna, what’s happening is truly terrifying for immigrant communities.

LikeLike

Rosaliene, what a beautiful post! 💕 I love the quotes from Brazilian poet, Rubens Jardim! How apt they seem for today!

We all live in fear. The Cabinet and Republican members of Congress live in fear! Federal judges seem very brave to stand up for the Constitution. The President says he will ignore Supreme Court rulings he doesn’t agree with. He seeks to unlawfully annex sovereign countries. the whole world needs to stand against him.

Those with student visas are afraid to open their mouths for fear their visas will be revoked. Churches and “Sanctuary Cities” are afraid to protect illegal immigrants. Green cards no longer provide freedom of speech and due process. New rules have been proposed to disenfranchise large numbers of voters.

Within just a few weeks of this administration, we are subject to the whims of madmen and madwomen, too. We are all at the mercy of their greed and hunger for power!

I published a poem on my blog today that condemns authoritarian rule and the destruction of democracy. It is my second post on the subject. Am I afraid? Yes, although I promised myself a long time ago not to live in fear. I don’t like to write about political topics, but I do love my country.

I can’t tell you as an immigrant, not to be afraid, but I can tell you that I admire you for speaking out. Take care, Rosaliene! 🌈 Have hope that sanity and democracy will return. I hope I live to see the day!

LikeLike

Cheryl, thanks very much for sharing your thoughts on the dangers we now face as a nation. We should all be afraid. More than ever, we need to care for and support each other regardless of what side of the political divide we may be on.

“all are involved! / all are consumed!”

~ Excerpt from poem “You are Involved” by Guyana’s Poet of Resistance Martin Carter (1927-1997).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rosaliene, I agree that all of us should care for and support each other. Diversity is the strength of our country. I love the quote!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I couldn’t agree more, Cheryl: Diversity is our strength.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the introduction to Jardim’s work, Rosaliene. His words and philosophy are so central to what we are living right now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure, Rebecca. Sadly, very little has changed over the years 😦

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not as far as dictatorships go. Absolute power corrupts absolutely.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely true, Rebecca. We are playing with fire.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“….even knowing that poetry is useless—as the poet Manoel de Barros enlighteningly said…”

To a capitalist, poetry is a pursuit that doesn’t make cents or dollars, yet the capitalist system will push back when the critical eye is on them.

Poetry sustains life. It brings hope, either through sharing disappointments, sharing joys, sharing one’s fears.. just being human.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So very true, Jasper. Thanks for sharing your thoughts.

LikeLiked by 1 person