Tags

Harassment at Work, Mabaruma/Guyana/South America, Public High School Teacher, Sexual harassment in the workplace, Shame and Self-forgiveness, When We Fail

In Chapter Sixteen of my work in Progress, I share my experience of sexual harassment as a public high school teacher by a government official. It was a period of my life that I had buried deep in my subconscious until my best friend insisted that my second novel should be about my life in the convent. Sadly, she passed away before I had completed the final revision of The Twisted Circle: A Novel, dedicated in her memory.

Although I had extensively explored my final year in the convent for the novel, I struggled over several months to complete this chapter. I even considered leaving it out altogether. To share the real-life experience of a dark period comes with its own challenges. To have failed and be rejected had left a deep emotional wound. To expose and uproot the shame requires self-forgiveness.

As I also share in Chapter Sixteen, harassment in the workplace is not limited to the male sexual pervert or predator. We can also suffer harassment from the female boss or colleague who, for a variety of reasons, perceive us as a threat. Sister Albertus, a fictitious name, was my female co-worker and tormentor.

Chapter Sixteen: Sexual Harassment as a Public High School Teacher

My move to our sister-convent in Guyana’s remote Northwest Region upended my life in unexpected ways. Up to that point, my five-year teaching experience was in a private parochial high school for girls run by the nuns with an all-female staff. The Northwest Government Secondary School in Mabaruma differed in every way: a male headteacher, male and female teaching staff, and a student body of girls and boys. After enjoying enclosed, individual classrooms, I now faced an open-floor plan with classrooms separated only by large blackboards.

Free education for all, I soon learned, did not mean an equal distribution of textbooks and materials for students and teaching staff nationwide. The shortages were glaring. I had to find creative ways to do my job. My small monthly stipend as a religious sister provided art materials for my students as well as sheets of cardboard for my geography projects.

The bombshell came in December at the end of the first term when the headmaster announced his transfer to another school.

“Until your new headteacher arrives in the New Year,” the headmaster said, “Sister Rosaliene will take over as acting head.”

Flabbergasted, I objected to a decision made without my consent. This was a new Guyana under an authoritarian government. I had no say in the matter. While the headmaster expressed confidence in my capacity to do the job because of my academic record, I regarded myself as unprepared to manage a school. Never mind we were a small staff of seven, including the secretary, with only 108 students.

Pushback to my acting appointment came from within our religious ranks: a white American nun serving in the Guyana Mission. I don’t recall her state of origin. About ten years older, she was our biology teacher with several years of teaching experience. I’ll call her Sister Albertus after Saint Albertus Magnus, also known as Saint Albert the Great, the Catholic patron saint of the natural sciences. In my estimation, she was an excellent teacher. I had a lot to learn from her. The students loved her. Having arrived in the region a year before I did, she was well-known and respected by the government officials in Mabaruma and the Indigenous peoples in the surrounding riverine villages.

The first sign of trouble occurred during a staff meeting in the second term. Sister Albertus criticized my lack of administrative skills, citing incidents of my failure to act appropriately. I went blank. Her derisive words disappeared into a void. The silence among the rest of the staff enveloped me. How wrong I was to think that we were getting along fine during the three months prior to my appointment as acting headteacher. I realized then that I could not count on her support in my new role.

I soon discovered that running a school, whatever its size, involved many day-to-day responsibilities, adding to my teacher workload: preparing the teachers’ class schedule, checking teachers’ lesson plans, general supervision, facilitating end-of-term and national certification exams, resolving student conflicts, maintaining the school and premises in good condition, requisitioning teaching materials and diverse school equipment, and ensuring that we received payment for our services from the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Georgetown. One month, I had to travel to the capital to collect our missing wages from the MOE payment division. Thankfully, it never happened again during my period as acting head. (In a twist of fate, the young man who assisted me that day would become my husband four years later.)

Moreover, directives from the MOE regarding both the curriculum and extracurricular activities could not be ignored, including student participation in the Guyana National Service (GNS). Then came the tricky part that required diplomatic skills I had yet to learn—dealing with the local government officials. The District Education Officer (DEO), the MOE representative for the region, was foremost among them. His residence was located within the perimeter of the school compound, close to the spot where Sister Albertus parked the convent jeep.

Since meeting the DEO shortly after my arrival in Mabaruma, I knew that he was the kind of man to avoid. An older man in his forties, he exuded the air of one who believed he was God’s gift to woman. What he lacked in height, physique, and looks, he made up for with his cocky gait and silky, seductive voice. His position as a senior government official also gave him the edge when dealing with young women under his control or influence. Young women like me.

That I was a religious sister was no impediment to him. “I’m a Don Juan,” he told me, without shame. As a celibate woman in my late twenties, with little experience in the games men play, I must’ve seemed an easy target to him. He knew nothing of my fighting spirit when faced with male abuse and violence. I knew nothing of the anger guarded deep within after years of emotional and physical abuse, as well as my sense of powerlessness against the injustices within my small world and beyond its frontiers.

One Monday morning, without prior notice, DEO Don Juan made his first visit to our school with me as acting head. I was teaching a class when our secretary brought the news. When I entered the office, he was seated in my chair, establishing control. I greeted him with a serious face. After perusing my face and bosom, he told me to have a seat. During the exchange that followed, I had to strain to hear his soft, purring voice. What’s worse, it became clear that the MOE had not yet assigned a new headteacher to our school. Only the Lord knew how long I would have to endure this detestable situation. I had to trust that He would give me the strength and courage to prevail.

At the end of the week, DEO Don Juan surprised me with yet another visit. This time, he came bearing gifts. Sports equipment to be precise. His face glowed with the glee of a schoolboy who had won a coveted prize as he unpacked the equipment on my desk. The individual items remain a blur.

“What’s all this?” I said, with a displeased tone and serious face.

“It’s for you…. There’s more where this came from.”

Refusing to fall victim to his ploy, I turned to the school secretary. “Did the headmaster requisition any sports equipment?”

“About a year ago, Sister. And we never got it.”

After playing his hand of tricks, Don Juan left.

The sports master was pleased to see the new acquisition. “Keep on doing whatever you’re doing, Sister.”

“What’s that supposed to mean? I haven’t done anything. When we spoke on Monday, I didn’t even mention sports equipment.”

Over the weekend, I replayed the scene over and over in my mind. My male colleague’s remarks troubled me: Keep on doing whatever you’re doing. As a woman, I was somehow responsible for the DEO’s behavior. No one could claim that I was dressed provocatively. My simple white habit, tucked in at the waist, concealed my neck, upper arms, and knees. I did not consider myself a beauty, nor a flirtatious or seductive type. For my students, male and female alike, I offered a smile and encouraging words. I reserved my hearty laughter for our group of young sisters-in-training. I missed having them close for emotional support.

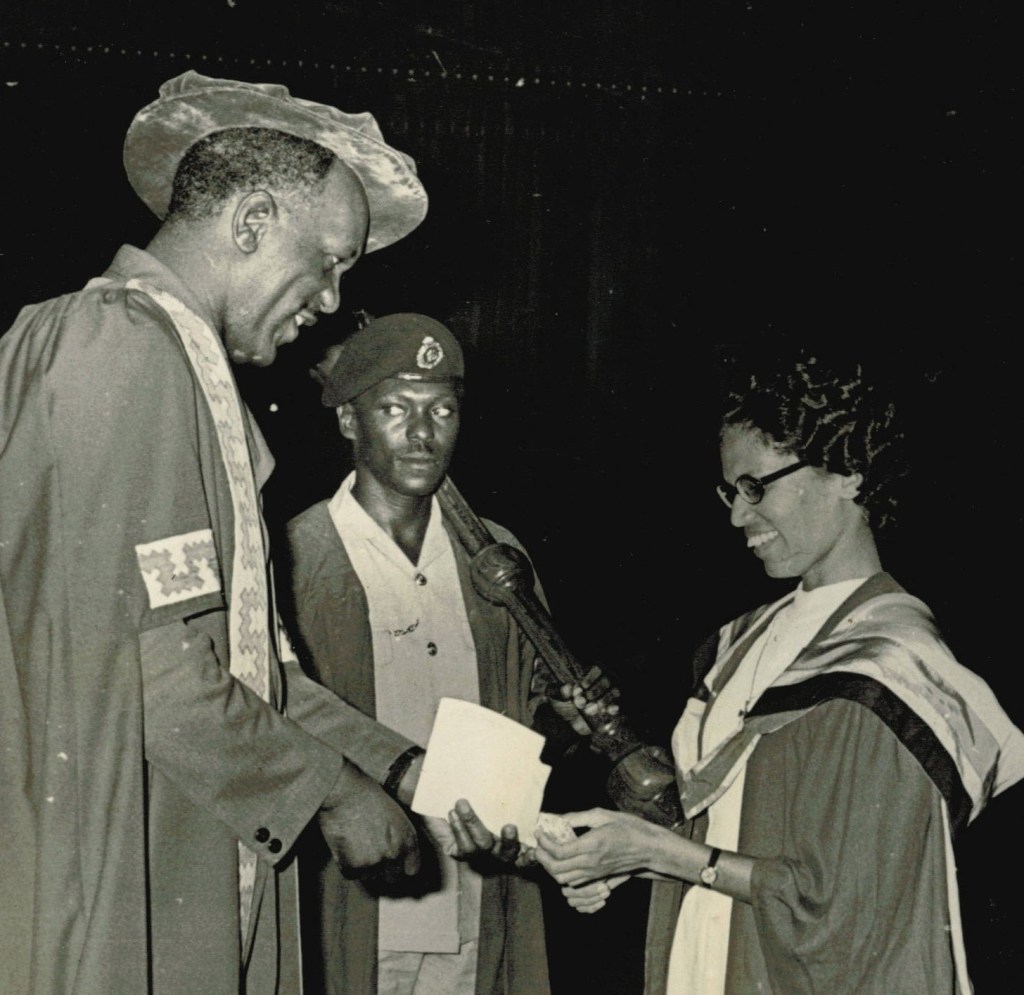

I should mention here that when I moved to our convent in the hinterlands, I no longer wore the religious head covering or veil. During the period I was an undergraduate at the University of Guyana, our local religious community received directives from the Provincialate in the United States regarding the optional use of the veil. While the Regional Coordinator and three members of her council led the way in going without the veil, I did not follow suit until my compulsory three-month stint in the Guyana National Service. After surviving the male gaze and commentary when dressed in the parrot-green paramilitary uniform, I gained confidence in exposing my short wavy hair.

Meanwhile, news of the sports equipment swept across the small government administrative center. The school secretary gave me the news on Monday morning. The headmaster of the Mabaruma Primary School was not at all happy. “He say is blatant favoritism,” she told me.

His negative response surprised me. I didn’t consider myself a rival. Besides, he had two daughters, both excellent students, studying at our school. I buried his remarks. Too many pressing matters needed my attention.

Whenever he was in Mabaruma, Don Juan never missed an opportunity to harass me with his sexual innuendos. Catching me outdoors, as I supervised the students in the playground, did not deter him. He slithered close to whisper in my ears, unnerving me. The scent of his cologne enveloped me.

“A woman like you shouldn’t be wasting away in a convent with frustrated old spinsters,” he told me on one encounter.

What a relief when the DEO was away visiting other schools in the region or in Georgetown! I could breathe freely. I didn’t have to look over my shoulder. I was unaware of anger coming to a boiling point deep within my core. Until the day a thirteen-year-old student in Form Two placed a firecracker under my chair. I’ll call him Raven because of his straight black hair that spilled over his forehead, partially hiding his shifty eyes.

Raven rarely spoke in the classroom. For reasons unknown, he did not like me. Whenever I spoke with him during class, he would mumble a reply without looking at me. After my efforts to connect with him failed, I learned to tolerate his sullen, devious behavior.

We had all gathered in the school hall for our Easter party. I was seated watching the celebration when a firecracker exploded near my feet. Filled with a rage released by the explosion, I leapt to my feet determined to catch the culprit. I pursued Raven out the side door into the playground. The sports master blocked my way.

“I’m going to kill that boy!” I shook with rage.

The sports master led me to my office. “Sit down, Sister. You need to calm down. Stay here while I get you some water.”

After returning with a glass of water, he stayed with me while my heartbeat and breathing returned to their normal state. “You can’t let Raven rile you up, Sister. That’s what he wants.”

My rage terrified me. My loss of control mortified me.

Rage of that magnitude knows no bounds. What a terrible example for my students! How could any parent trust me with their child? I was a failure. I was worthless.

As often happened, when I got home later that afternoon, the sisters had already heard about my outburst. The reactions to my shameful behavior from my House Coordinator and the Mabaruma community remain a blur. Perhaps, DEO Don Juan knew then that I was not a woman to meddle with.

What a win this must’ve been for Sister Albertus! What better proof of my failure as a school administrator.

When the Regional Coordinator and a council member visited our community a month later, I had no idea of Albertus’ long list of my transgressions, recorded in her black diary. During a meeting to discuss the conflict between us, Albertus also accused me of flirting with all the men, even our septuagenarian parish priest. My way of talking and smiling with men was “not becoming of a nun,” she said. Not so, her exclusive relationship with our assistant parish priest, Father Mahseer, an Indian Jesuit priest in his forties. (I described their relationship in Chapter Fourteen: The Men of God.) Did our parish priests defend my reputation?

After the confrontation with Albertus, I spoke in private with our Regional Coordinator about the DEO’s harassment. On her advice, I made an appointment to speak with his boss, the Chief Education Officer (CEO) at the Ministry of Education in Georgetown. At the embarrassing meeting with the CEO, I was shocked to learn that Sister Albertus had already spoken to him about being harassed. She never mentioned that she was also a victim. Did this begin before my arrival in Mabaruma? Was Don Juan still harassing her? I never asked her or the CEO. Since a cold front had settled between us, we never talked about our shared experience.

Another surprise awaited me that day after I left the CEO’s office. While walking along the corridor on my way out, I never expected to come face-to-face with DEO Don Juan. He couldn’t let me go by without a word. The CEO must’ve already told him about Sister Albertus’ accusation.

“I’m glad you’re here,” he said with his customary seductive smile and silky tone. “The CEO will see for himself what I had to contend with.”

Only Don Juan knew what he had to contend with. I was no Marilyn Monroe or Farrah Fawcett. His sexual fantasies were beyond my control. I gave thanks to the Lord when the CEO relieved him of his duties in Mabaruma.

But my life did not return to normalcy. Albertus had broken my spirit and robbed me of joy. My smile was flirtatious. I was a failure as a religious woman. I questioned every administrative decision I made. I questioned my competence as a teacher. My worthlessness was evident.

During the final school term, the overworked engine of the convent jeep finally died, forcing me and Albertus to walk to and from school. The five-mile (eight-kilometer) walk took me an hour or more. Judging from Albertus’ behavior, the meeting with the Regional Coordinator did not achieve any reconciliation between us. From the very first day on foot, she left for Mabaruma without me. She did the same at the end of the school day.

The hot and humid afternoon air made the walk home more difficult than the cool early morning temperatures. Even the birds took refuge from the heat. An oppressive silence hung over the dense trees and bushes along the unpaved, red, two-lane-wide roadway. One section across the valley stretched for about a mile without any bend in the road, making it seem like an eternity ahead. Never had I felt so alone in the world…and so lonely. Did anyone care if I lived or died? God, in whom I placed my trust, seemed so distant.

My situation seemed hopeless. Sister Albertus held power within the religious community. I was a nobody to be crushed like sugarcane husk. To save myself, I had to leave the oppressive jungle that hemmed me in on all sides. I saw no other way. I was withering inside. My life had lost meaning and joy.

I held on until the end of the school year, fulfilling my responsibilities as acting headteacher. After advising the House Coordinator and other sisters in the Interior community, I packed the two suitcases—one with my textbooks, the other with my personal effects—that I had arrived with and flew out of Mabaruma. Never to return.

Back in Georgetown, the comrade at the Ministry of Education (MOE) responsible for teacher placements refused to transfer me back to a school in the capital. I told her that I had moved out of the sister-convent in the region and would have nowhere to live. “No problem,” she said. “You can live at the teachers’ hostel in Mabaruma.” I did not mention the strained relationship with the school’s biology teacher. Convent affairs between the nuns were not her concern.

My career in the teaching profession ended with a whimper. Returning to Mabaruma was not an option for me. My departure didn’t matter to the MOE. The Catholic Church, critical of the authoritarian regime, had become an enemy of the State.

“What will you do now?” the Regional Coordinator said when I told her the news.

I had no idea. I was trapped in a dark place.

My fate now rested in the hands of my religious superiors. Their verdict: I lacked emotional maturity for handling conflict situations in community life. Their sentence: It was best for me to leave the community. Conflict situations were a part of living with others.

I had failed to measure up. I did not belong. I was useless to them.

Fear gripped me at night with thoughts of returning to secular life.

This resonates with me, Rosaliene, and reading your story helped me further understand my own. Looking back, I wish someone had helped me explore the anger I had buried deep inside myself, that anger that made me vulnerable.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Madeline, I’m glad that you’re able to connect with my story. I’m still coming to terms with what I consider as justified anger.

LikeLike

Another gripping, honest, and insightful episode. It is a wonder that you stayed in the order as long as you did. Sister Albertus will never know the honour you gave her in your choice of pseudonym

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Derrick. Her chosen religious name, after an early Christian martyr, was even more honorable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rosaliene, a VERY well-written, compelling, heartbreaking chapter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Dave, for your kind comment. I find that writing creative non-fiction is even more challenging than fiction.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’ve dealt with a lot. A whole lot. With strength that maybe you didn’t know you had, you landed on your feet.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Neil, it’s with adversity that we find our strength. It took several years for me to land on my feet again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

People can be cruel, especially in an institutional setting, doing their best to tear others down. Sorry you had to go through that and that you did not get the support you needed. Glad that the whole process made you even stronger. Thanks for sharing and have a great Sunday Rosaliene. Allan

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Allan. Adversity is an excellent teacher. I wish we could be less cruel towards each other.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m certain this will help many others who’ve shared similar experiences and likey have not voiced them out loud. I especially love that you mention forgiving yourself. My motto when it comes to trauma is “reject any guilt”. I pray the book does well!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for your good wishes, Tammy! It’s my hope that our stories as Caribbean women can illuminate how much has changed since my youth, yet much remains the same.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Rosaliene, what a story and what a life you have had. You are stronger for all the struggles! 🤗🌹🙏

LikeLiked by 2 people

I am, indeed, much stronger, Ashley! 🙂 ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

I found it sad that the blame of the situation landed on you, when you were doing a difficult job as head teacher for the first time. Don Juan and jealous Sister A sure made it harder. Harassment is woven into society in a way that puts women into a challenging position of receiving no empathy when they refuse men’s advances and ugly labels if they do.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Rebecca, my younger self appreciates your supportive remarks ❤ What's also sad is that what should've been an opportunity for professional growth became a nightmare.

From what I've observed in California, there are now laws to prevent sexual and other harassment in the workplace. Under the California Code, employers with at least five employees or contractors must provide sexual harassment prevention training to all employees, including supervisory and non-supervisory employees, every two years. My hope is that this is making a difference.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m glad to hear of the laws in CA educating people in businesses so such harassment can be avoided and discouraged.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rebecca, do you have similar laws in Wisconsin?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great question, Rosaliene. We have laws to protect people from sexual harassment, but not laws to mandate training.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the feedback, Rebecca.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was a heartbreaking yet fascinating read, Rosaliene! Demonstrates well the toxic environment of patriarchal authoritarianism. I’m glad you left when you did. I’m looking forward to the next chapter!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much for your kind praise, Mara! Here in the US, we know not what we do in opening the door to patriarchal authoritarianism.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, those were dark days. Very difficult for women in those days, when blaming the victim was all too common. Your previous experiences with abusers left you with few tools, and you went into self blame, echoing the victim blaming you received.

There are forces now who wish to return to those days, when accountability was scant, and perpetrators barely received a slap on the hand.

Your stories are important, for younger women to be able to understand what life was actually like, and not the Instagram happy homemaker fantasy they spin.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Your comments are spot on, Tamara! If only I knew then what I know now.

It was the call to “Make America Great Again,” a return to the 1950s and 1960s, that compelled me to tell our stories. The “happy homemaker” may have been true for women in the elite class, but definitely not true for the majority of working class women.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Exactly. I know from what my mother and grandmother have said, it wasn’t easy. Women were easy prey and had to bear the brunt of the ills.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, Rosaliene. What a difficult time for you! And none of it of your own making. The decision to install you as acting head teacher without your consent was so wrong. They set you up for hardship and I have no doubt you suffered PTSD as a result of the many troubles coming at your from multiple directions. It’s very understandable you reacted that way after the firecracker exploded next to you. I can only imagine how confused and at-sea you felt at that time, and am glad to know you regained your equilibrium and grew into the woman you are today.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Tracy, my younger self appreciates your understanding of those dark days. It took years to regain my equilibrium. Adversity comes in all forms, calling on us to find our strength to overcome and, hopefully, triumph.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is a shameful, and far too common story, when women doing their best to do good for the betterment of their community, who may be without a strong support system of their own, are taken advantage of by those in leadership positions. Your strength and compassion are admirable, Rosaliene. Thank you for sharing your book links. 👍🏻

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much for your kind praise, Michele ❤ It took years to accept that there will always be those who are threatened by or jealous of our achievements.

I couldn't miss the opportunity to promote my novel by sharing the link 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re very welcome. It is my honor to read your stories. 😊 I am getting there as far as accepting that behavior. It is confusing and somethings will never make sense but best to accept and carry on. I am glad you did! It’s in my inbox.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Michele, such behavior makes total sense to those who put us down and torment our lives. As an international trade professional in Brazil, I’ve witnessed the fall of those individuals.

I’m not sure what’s in your inbox.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am sure you’ve seen plenty in that profession! Your book is in my Amazon cart. Apologies for my cryptic note.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much for purchasing a copy, Michele! Hope you find it an enjoyable read 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh my gosh Rosaliene, I truly admire your strength and perseverance. Now sistah, let me say that this was one of the things that blew me away:

“Free education for all, I soon learned, did not mean an equal distribution of textbooks and materials for students and teaching staff nationwide. The shortages were glaring. I had to find creative ways to do my job.” I find this mind-blowing for starters my friend. 😲

Next, I have heard some horror stories surrounding certain religious administrations, but your religious superiors were, excuse my language, assholes. Typically we would never believe that such behavior and mindsets would come from convent affairs like yours, but it seems like you were liberated once you left their authoritarian regime, even if the secular life scared you. I applaud your bravery my friend. 🥰🙏🏼😊👏🏼😘

LikeLiked by 2 people

I appreciate your kind praise, Kym ❤ We never know our strength until we are truly tested under fire. Mind you, it's no fun being in the trenches. Today, I can regard Sister Albertus as an instrument in setting me free from the stifling convent life. The Lord writes with crooked lines, a nun once told me.

I'm glad that you picked up on the economic cost of free education for a small nation. Mandate/Project 2025 has drawn up proposals for the elimination of the federal Department of Education and allocation of the federal funds directly to states without strings, eliminating the need for federal and state bureaucrats (pp. 319-362). Only the gods know how this will affect teachers and schools in poor and marginalized communities.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sistah Rosaliene thank God you escaped those trenches! 🙏🏼 But to eliminate any part of the educational system is ludicrous and it simply amazes me the level of ignorance people subject themselves to. I think we already have an idea how this will affect schools, teachers and the children themselves. Ignorance is simply dangerous when it is powered by authoritative ignorance. 😣🤷🏻♀️😫

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kym, may the gods protect us if they get their way!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rosaliene, I am so there with you. My prayer is, that those of us standing in the gap fast, pray, and trust God that He still has control over this and thus he has a plan for His children who try to remain obedient and penalties for those who intentionally don’t. Bless you my friend! 😘🙏🏼🥰💖😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Blessings to you, too, my friend ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

🤗💖🙏🏼

LikeLiked by 1 person

A den of vipers. You were surrounded on all sides, with no ounce of support. I have seen these situations, Rosaliene. Deceit sometimes has no boundaries. Your behavior was admirable. I am so sorry you had to endure this. For what it is worth, I was captivated by the chapter and look forward to reading the book.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dr. Stein, I’m so glad that you found the chapter captivating 🙂 Much appreciated ❤ I was too young to perceive the deceit at play. We learn and grow.

LikeLike

This was common workplace conduct at the time. Few working women were left untouched by sexual harassment. I’m sorry for your experiences, Rosaliene. Hopefully, things are better today.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mary, I also believed that this was no longer a common workplace conduct, until the #MeToo movement exploded here in the USA in 2017. I’m in a much better place today since I’ve been working from home since 2007.

LikeLike

You’ve been through a lot Rosaliene, labelled as someone you are not and your innocent smile being misinterpreted is really annoying, but you tolerated all, what a character!

You obviously have a vast experience of the convent as well, no wonder you’ve put that in writing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Zet Ar, thanks very much for your kind remarks ❤ I was too young to appreciate that living among women of different ages, background, and personalities would involve conflict relationships.

LikeLiked by 1 person

wow – the red of that earth!

Linda xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Linda, thanks for dropping by 🙂 That red dirt road through the jungle is symbolic of my journey during that period in my life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

it’s very poignant! xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

An important and brave article; I love the way you draw upon your own experiences. This totally resonates with me. Thanks for sharing 💙

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Ada. I’m glad to know that my experience resonates with you. As women, we’re forced to accept a lot of male abuse in the workplace to hold on to our jobs. To see it overtly displayed in the political sphere is very disturbing. Blessings ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your honesty makes your writing powerful. We sure can be hard on ourselves, especially when we’re young and vulnerable. I’m sorry you went through this, but thankful for your courage, healing and self-forgiveness. Your story has much potential to help others, too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

JoAnna, thanks very much for your kind and supportive comments ❤ It is my hope that the stories I tell will make a difference in some other woman's life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So moving, it leaves me speechless. You have demonstrated remarkable strength and I appreciate you writing this with transparency.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rusty, thanks very much for your kind praise ❤ It was not an easy story to share.

LikeLike

I echo Rusty’s sentiments toward your character and writing, Rosaliene. You were pushed into an impossible situation with no support, and only harassment, gossip, and insufficient resources as companions.

Despite having no administrative experience to draw on in the role, I feel the way you managed yourself was quite remarkable. Your reply to the “keep doing what you’re doing” comment was brilliant; it’s just a shame that so much sexual harassment occurs, and that the system enables it. I actually was surprised to read that Don Juan was let go given the general societal view of men as superior. I too appreciate the honesty in sharing about your experience of rage; I have no doubt your self-reflection on that would exceed any sanctions that could ever be imposed externally.

Despite the unenviable circumstances you write of, I enjoyed reading this excerpt. I’ve commented before on the quality of your writing. And while I realize the story is true, the way you end it adds a strong element of suspense about what comes next in this pivotal time. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Steve, thanks very much for your feedback about my writing. Much appreciated ❤

I will have to make it clear that Don Juan was not let go. He was transferred to another district, thereby enabling him to continue harassing other young women. Much like the priests in the Catholic Church.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh my, I’m sorry, in my reading I misinterpreted that.

That is too much like what has happened in the church here with historical sexual harassment and assaults, and rampantly so in the Indian Residential Schools system.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No need to apologize, Steve. I’ve already added a note to the chapter for better clarification about Don Juan’s fate. Readers spot things that we don’t during our revision process.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rosaliene. I bless you for undertaking this soul searching journey to freedom – bring it all to the cross and hear the truth that Jesus speaks over you, beloved woman of God.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks very much, Dawn ❤ I count on Him in showing me the way forward.

LikeLiked by 1 person