Tags

Afro-Guyanese Washerwoman, British Guiana (Guyana)/South America, Good Neighbors, Guyanese Black-pudding & Souse, Self-reliant woman

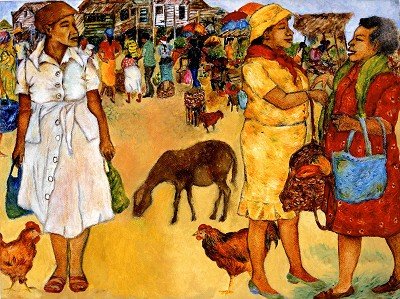

Photo Credit: Joy Richardson (Market Series)

Chapter Four of my work in progress presents the second portrait of a woman in my life. Auntie Katie was an inextricable part of my childhood. She lived in the adjacent flat in the tenement yard, where we shared the same toilet and bathroom. Unlike other neighbors in the yard, she did not complain if we were too noisy. Perhaps, she considered that we already had our fair share of corporal punishment.

For some reason, she tolerated my curiosity and treated me with kindness. I liked and respected her. In her simple and quiet manner, she taught me that the color of our skin did not matter. What was in our heart mattered. How we treated others, even the little ones, mattered. Though she has been long gone from the world of the living, she remains close to my heart.

In Chapter One of my debut novel, Under the Tamarind Tree, she makes a small appearance as herself. More importantly, she became the inspiration for my most beloved character, Mama Chips, the protagonist’s surrogate mother following his mother’s death when he was thirteen years old.

The period described in Chapter Four is the 1950s and 1960s in then British Guiana.

Chapter Four: Auntie Katie – A Good Neighbor

Auntie Katie—as Mother and we children called her—lived next-door in the bottom flat of our two-story, wooden unit in the tenement yard. After Mother, she was the second most influential adult female during my formative years. A childless widow who lived alone, she seemed ancient to a kid, though she was probably only in her forties. She was an independent, self-reliant woman who didn’t have to put up with an abusive husband like Father. Was that the reason why she had never remarried?

Quite a go-getter when it came to making money to support herself, she was always busy with some task. She spent most of her time washing laundry for clients in the neighborhood. Her wooden wash basin, about two-feet wide and one-foot deep, together with a wooden scrubbing board, sat at the foot of the backstairs where she worked. The cuticles of her fingernails were puffy after years of using the harsh, laundry bar soap. As a curious child, I would watch her apply a soothing balm to the cuticles whenever they became inflamed. She never complained of any pain.

Her other source of income came from the sale of black-pudding, sweet potato pudding, and souse. Making the sausage is messy work. It involves working with the pig’s large intestines and cow’s blood. The intestines or runners, as they are called, are stuffed with seasoned boiled rice or grated sweet potato mixed in cow’s blood, tied to avoid leakage, and then boiled in a large pot. As a kid, I preferred the sweet potato pudding, but the rice-filled pudding became my favorite when I grew older.

While preparing these savory sausages, Auntie Katie always kept her kitchen door closed. The narrow hallway, leading from our flat to the toilet and bathroom that we shared with Auntie Katie, went by her kitchen door. One lucky day on the way to the toilet, I noticed that her kitchen door stood slightly ajar and sneaked a peep. All I spied that day looked like long, huge, slithery, pale-skin worms. No blood.

Black-pudding was always served with souse. Don’t ask me why. Another time-consuming dish to prepare, souse is made with pig face and ears, pig trotters, and pig shoulder steak. They are all boiled until tender. After draining and cooling, the meat is seasoned with onions, pepper, shallot (spring onion), celery leaves, and cucumber, then left to marinate for at least three to four hours in a mixture of lime or lemon juice, vinegar, and water. Auntie Katie’s black-pudding and souse were a special treat for our family on a Saturday evening.

Added to doing other people’s laundry and selling her specialty dishes, Auntie Katie straightened the hair of her young female black clients. Although she worked outdoors in the backyard, we could not avoid the horrid smell of burning hair. In those days, she heated the metal comb over a coal pot.

Used for outdoor cooking, especially in rural areas, the coal pot was an earthenware or cast-iron stove with a top basin, about six inches deep and a foot in diameter, for holding the hot coals. The ash fell through holes in the basin into the hollow cylindrical base about six inches deep. Holes in the base, used for removal of the ash, allowed for air flow.

Straight hair, like that of white people, was the preferred hairstyle for black women. I was not exempt from such vanity. Beginning in my teenage years, I began straightening my wavy hair with large plastic hair rollers. At nights, I endured sleeping with a headful of rollers. The things we women do to achieve the beauty standards of our day!

Every Saturday afternoon, Auntie Katie dressed up in her best outfits—with matching hat, handbag, shoes, and costume jewelry—to attend the African Methodist Episcopal Church, called the AME Church, just two blocks away from home. An active church member, she also took part in church events to raise funds for the poor or to go on excursions to places outside of Georgetown, the capital city. She took Mother, me, and two other siblings—old enough to know not to give the grownups any trouble—on some of the excursions. On one occasion, when I was six or seven years old, Mother and I joined Auntie Katie on a two-week stay with her relatives in New Amsterdam, the second largest urban area, about fifty-eight miles by rail from Georgetown.

Reflecting now on that period of our joint lives as neighbors, I believe that Auntie Katie, in her own little way, did what she could to give Mother time away from her hellish day-to-day life.

To help Mother raise money for the downpayment of a newer model of the Singer sewing machine, the one with the foot pedal, Auntie Katie invited Mother to join her box-hand with her trusted friends from the AME Church. The box-hand is a savings scheme in which each participant makes a fixed weekly or monthly contribution. The total sum received in the box-hand is given to the person when it is her turn to ‘draw.’ Mother kept a record of her contributions and the group’s ‘drawings’ on a calendar hanging on the kitchen wall. She and Auntie Katie had a terrible argument and falling-out over Mother’s turn to receive the box-hand. Good friends fall out, I learned then, and can make up again.

Auntie Katie and Mother disagreed about the best man to lead our country to independence from Britain. Auntie Katie was a staunch supporter of Forbes Burnham, the leader of the majority black political party. She raised money for his political party through the sale of her black-pudding and souse at the party’s fundraising events. I recall an incidence when Burnham, the British-trained lawyer and party leader—he would have been in his mid-thirties at the time—visited her flat to collect his black-pudding order. For her as a black woman, he was the black Moses who had been raised up by God to free the Guianese black people from white oppression. A gifted speaker who loved to quote the Bible, he enthralled her with his charisma.

Mother did not like him. “He got too much sweet-mouth,” Mother told Auntie Katie, referring to Burnham’s flattering talk to win people over to his side.

Despite their differences, Auntie Katie looked out for Mother and for us children. When Mother had to deliver a client’s dresses or buy sewing materials, Auntie Katie would keep an eye on us. The incident that sealed my high regard for her occurred one Christmas season, just two days before Christmas Day. Mother was too busy with her sewing to take me, my brother, and sister—the three eldest children—to visit Santa Claus, as she had promised us for good behavior. Auntie Katie offered to take us. Off we went by bus to the downtown shopping area to the two top department stores, Bookers Stores and Fogarty’s, to pay for and receive our Christmas presents from Santa Claus himself. What joy for a poor kid!

Although the Burnham government’s restrictive policies affected her as a poor working-class woman, Auntie Katie remained a loyal party member to the end of her life. When they attain power, the men that we women support, in our joint struggle for freedom and justice, do not always have our best interests at heart.

I really like that picture “Market Greetings”. It has a real sense of vibrant life in, perhaps, the centre of a town or a city community.

LikeLiked by 2 people

John, I’m so glad you like my picture choice 🙂 I couldn’t find a decent photo or painting of a West Indian/Caribbean washerwoman, but found this painting very vibrant, indeed.

LikeLike

I’ve never been there, but this picture may be the next best thing!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

She certainly does sound like a good neighbor. I enjoyed reading your chapter about her.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks very much, Nemorino 🙂

LikeLike

Another engrossing chapter in what is much more than a tribute to Auntie Katie – a memoir of an era. Black pudding and souse looks really appetising

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Derrick 🙂 It was definitely a different era. I don’t miss souse, but there are times I could do with a slice or two of black-pudding 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

The picture is lovely and the chapter fascinating 😘

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Luisa 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure ❣️ Cheers

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aunty Katie sounds amazing.

LikeLiked by 2 people

She was, indeed, Diana! Thanks for dropping by 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your Auntie Katie was a very special person, and your words are a lovely tribute to her memory, Rosaliene. Thank you for sharing. ❤️

LikeLiked by 3 people

My pleasure, Sunnyside 🙂 She was special to our family and those who knew her ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another wonderful post, Rosaliene. Thank you for sharing it here. Also, the painting, Market Greetings is amazing, so colourful, vibrant! 🌹🙋♂️

LikeLiked by 3 people

My pleasure, Ashley! Thanks very much 🙂 So glad you like the painting. I came across Joy Richardson’s work by chance.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A great tribute to Auntie Katie. It is always nice to recognize those who are important in our lives. Happy Sunday Rosaliene. Allan

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks very much, Allan 🙂 It was a beautiful Sunday for being outdoors 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great memories of a great role model. I remember the hot iron my mother and sister used back in the day.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, John 🙂 These days, there are better hair straighteners and products.

LikeLike

Great descriptive writing and character portrayal (your Aunt Katie), Rosaliene!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Dave!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very poignant and lyrical, Rosaliene.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Kim 🙂 Hope that your bookstore is doing well.

LikeLike

What a loving tribute to Auntie Katie. I’m thinking the example of this industrious, independent woman was important to you in showing different ways a woman could live her life. Key community for you and your family.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Rebecca 🙂 You’re spot on when you note that her way of life opened new possibilities for me as a girl growing up in a man’s world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So glad her example and support was there for you. Several key neighborhood women were important to me too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rebecca, I’m happy to know that you, too, had women like Auntie Katie in your young life. As children, we often overlook them or didn’t appreciate that they were looking out for us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As an adult, I have thanked the woman who let me visit her each day before school since my mom had to get to work early.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How wonderful that you had such an opportunity, Rebecca!

LikeLiked by 1 person

She was an excellent friend and neighbor to your family. That sort of neighborliness wasn’t and isn’t all that common.

LikeLiked by 3 people

As Derrick observed, Neil, that was a different era. Also, as members of the poor working-class, our survival depended upon looking out for each other.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That the world survives despite our imperfections is surely due to the anonymous goodness of such wonderful people as Auntie Katie. Her influence on you may well be reflected in your own work to repair the world, Rosaliene. Thank you for introducing her. Such names should not be forgotten.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Dr. Stein, I agree with your comment about the “anonymous goodness” of people like Auntie Katie. They continue to walk among us ❤

I don't believe that I can repair the world. I believe I can make a difference in someone's life, just as Auntie Katie and countless of others have done for me over the years.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Every kid should have an Auntie Katie! I love the comment your mom made about the politician having too much sweet-mouth. Well said.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Mara 🙂 I agree that every kid should have an Auntie Katie!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, I love your writing voice, you draw us right in to the story, so we see and feel what you are showing us. I love the little details you add, like the smell of the burning hair, not that’s something pleasant, but by evoking the senses, we’re there with you!

A wonderful chapter about a wonderful woman who helped your family!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Tamara, thanks very much for your kind comments about my writing voice and style 🙂 I still question myself about getting it right.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well dear lady, I think you’re nailing it!!

LikeLike

Yay!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, what a privilege to meet Auntie Katie in this chapter! I’m so glad you had her in your life. And that stroll through the kitchen and neighborhood, all those visual descriptions, that was a delight

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much for your kind comments, Shannon! So glad that you found the descriptions delightful 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Summarily: ‘In Memory of Auntie Katie’

Great memories indeed!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Zet Ar!

LikeLike

I’m a big fan of Auntie Katie and was so sad to read the final paragraph. She’d sold her puddings to raise money for the candidate who later did nothing to elevate her life. 😦

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Tracy 🙂 Sadly, that so often happens with the men we raise up as our leaders 😦

LikeLiked by 1 person

Onward!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is so refreshing, my dear friend. Yesterday I prepared souse for a great-niece’s 21st and only the grown ups participated in this most delicious dish! The young ones, some of them tasted but most of them think it is too much bone and far too little meat! I am forwarding this chapter to all nine of them! Thank you.

Awaiting the other chapters and the Book!

LikeLiked by 2 people

George, thanks very much for reading and sharing this chapter with your relatives 🙂 I can well understand that the young ones weren’t impressed on trying souse. It’s an acquired taste.

LikeLike

A touching personal piece and one that reminded me of a dear aunt I lost a few years ago. Is your book available?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Michele, I’m so glad that you could connect with Auntie Katie’s story 🙂 My book is not yet available as it’s a work-in-progress.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh yes, my aunt Linda Lee was/still is a treasure to me. 💞 Their impactful lessons stay with us. Best wishes on your WIP. Looks like you are making great progress!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Michele, it’s wonderful to have such female role models in our lives ❤ I'm currently working on my seventh of eight portraits of Guyanese women. One of them is a naturalized American-Guyanese, a remarkable woman unknown to the majority of American women of younger generations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am delighted to be following your blog. 🙏🏻

LikeLiked by 1 person

That means a lot to me, Michele ❤ Thanks 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am so glad. I am cheering you on! ✍🏻🙌🏻

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aunt Katie had what seems to be like a rare combination of skills, industriousness, and kindness. The lesson that friends can disagree strongly, but still care for each other and support each other is an important one we need to remember. I’m thankful she was such a big part of your life. Of less importance is the memory I have as a white girl with curly hair and wanting it to be straight as that was the style in the late 60s and early 70s. Now, I like the little bit of curl I have left.

LikeLiked by 2 people

JoAnna, it’s strange how that lesson of disagreement between friends has stayed with me. On the other hand, I’ve learned over the years that some friendships don’t withstand irreconcilable differences.

It’s been interesting to observe the wavy/curly hair trend among women with straight hair.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It helps if friends can listen with respect. But sometimes we have to let them go.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can’t wait for your book!!!! You have a great way of drawing us in.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Belladonna!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m fascinated by the hair straightener. For whatever reason, I used to burn my hair (one strand at a time) with the cigarette lighter in our car when I was young. It stunk. Congrats on your continued progress, Rosaliene!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Crystal! We do crazy things as kids 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much. Aunt Katie was a strong person in all senses. I will read your earlier posts . Regards, Lakshmi

LikeLiked by 2 people

My pleasure, Lakshmi. Thanks for dropping by and signing up to follow my blog 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing!!.. “Life gives us brief moments with another, but sometimes in those brief moments we get memories that last a lifetime, So live that your memories will be part of your happiness.” (Author Unknown)… 🙂

Hope all is well in your part of the universe and until we meet again…..

May the dreams you hold dearest

Be those which come true

May the kindness you spread

Keep returning to you

(Irish Saying)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dutch, thanks very much for dropping by and sharing your thoughts 🙂

LikeLike

What wonderful stories you tell of Aunt Katie and your family. People like her live and warm our hearts long after she has passed on.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dwight, thanks for reading. So glad you enjoyed Aunt Katie’s story 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are welcome.

LikeLiked by 1 person