Tags

British Guiana (Guyana)/South America, Corporal punishment, Domestic violence, Intimate Partner Violence (IPV), Political Violence

Photo Credit: KPBS (Williams Rawlins for NPR)

As I shared in my May 23rd post on getting my creative mojo back, I have resumed work on my writing project about women of agency. Revision of the completed draft of Part One, set in Guyana, is steadily moving forward. I struggled with Chapter Two: The Violence of Men.

When I first presented this chapter to my writers’ critique group in August 2019, I discovered that it was an uncomfortable subject for the male members of our group. I could see the rage in the eyes of my writing friend seated directly across from me on the other side of the table.

“I’m not a violent man,” he told me, struggling to restrain his anger. “I defended my mother against our psychotic father… I protected her.”

Taken aback, I said: “I’m speaking in general terms.”

Another male member of our group was more measured with his response: “Rough content, but so is life.”

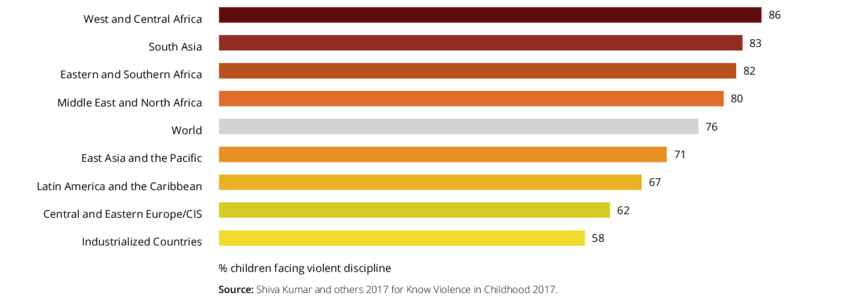

Guyana’s First National Survey on Gender-Based Violence, launched in November 2019, revealed that more than half (55%) of all women experienced at least one form of violence. More than one in ten had experienced physical and/or sexual violence from a male partner in the previous 12 months. One in every two women in Guyana has or will experience Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) in their lifetime. Moreover, one in five (20%) women has experienced non-partner sexual abuse in their lifetime; thirteen percent (13%) experienced this abuse before the age of 18.

We live in a world still dominated by the heterosexual male. All men are not violent. All women are not nurturers. I’m considering changing the Chapter heading to “Violence as Humanity’s Default System.” What do you think?

Chapter Two: The Violence of Men

Violence in all its manifestations has been a part of our lives worldwide. No country is immune. In former European colonial societies built by slave and indentured labor, like British Guiana, violence was an essential means of control. Such violence against the human body and spirit did not simply vanish into the ether at the end of slavery and colonialism. It reverberates within the society where the strong continue to batter the weak and more vulnerable: women, children, the aged, and the marginalized.

Chart Credit: ResearchGate, Ending Violence in Childhood Global Report 2017

From an early age, I experienced and witnessed the violence of men while growing up in one of many working-class tenement yards across the capital. Father ruled with verbal and physical abuse. Playing in the drawing room and touching his treasured record and book collections featured high on his litany of offenses. He beat us for being disobedient. He beat us for being too noisy or fighting among ourselves. He beat us for stealing sugar or sweetened condensed milk. The local wild cane—made from the tall, tough-stemmed, arrow-grass reed plant—was his weapon of choice. A blow from the wild cane stung our tender flesh, leaving a red mark that later faded. Hiding the wild cane made matters worse, as Father would grab his leather belt which wielded a more severe blow. I developed an abscess on my right arm after such a blow. Once, I tried escaping licks, as we called it, by hiding under the bunk bed. Bad idea. I got double the number of lashes.

When Father came home drunk, things could get ugly for everybody, including Mother. Father did not strike her. Similar in body weight, she never cowered. She stood firm, ready to fight back. Instead, he lambasted her with the most vulgar Creole language.

“Scunt, rasshole,” he said, hurling the demeaning words at her.

Mother responded in similar coarse language.

“One-a-these days, I going bash in your mouth.”

“Try it,” she told him.

One of my earliest memories of Father’s drunken rage was the time he threw the pot of cooked food out the kitchen window. For some reason, it was not done to his liking. I must have been between three and four years old. I huddled in a corner out of sight. Did Father hate us? Were we a burden to him? These were questions I asked myself as I grew older.

He and Mother fought constantly about money. In those days, Father worked as a clerk for a small, family-owned, importer and wholesale firm. The money he gave her each month was never enough to feed our growing family.

“But you always got money to drink with your friends.”

“Is what you saying?” Father would snap back. “A hardworking man can’t even take a drink with he friends?”

To help with expenses, Mother took a Singer’s sewing course. Grandfather paid for the course and bought her a table model of the Singer sewing machine with a hand crank. (I didn’t know it then, but Grandfather was our Guardian Angel.) Added to her chores of caring for us kids, cooking, washing clothes, and house cleaning, she began working from home as a seamstress. From as early as six years old, I became her helper in caring for my younger siblings and going on errands to get everyday foodstuff—like margarine, peanut butter, salt, and sugar sold by the ounce in greaseproof paper packages or paper bags—at the Chinese cake-shop at the corner of our block. Fearful of getting licks, I never told her about the time the shopkeeper’s young black assistant put me to sit on the countertop and put his hand in my panty.

At eight years old, I learned the truth about my birth. In the tenement yard with ten family units—two two-story wooden houses with four flats each and two small cottages—we children were privy to the boisterous exchanges between the adults. Mother got into an argument with a female tenant after my seven-year-old brother broke her windowpane while playing cricket.

“Your husband only marry you ‘cause you did pregnant,” the neighbor told Mother, straight up in her face.

I dared not ask Mother if it were true. We did not put our mouth in big people business, as we say in the local dialect. Later, Mother’s youngest sister, Auntie Baby, confirmed the accusation. Oh, the guilt I carried from thence forward, believing that I was the cause of Mother’s unhappy marriage!

In her elder years, Mother became more open about her early life. She and Father were thrown together by circumstances not of their doing. Her younger sister stole her boyfriend, the guy she had wanted to marry. The girl Father loved was my mother’s cousin—Grandfather’s only daughter. At the time, Father worked at Grandfather’s bakery. Determined to end her daughter’s undesirable relationship with a penniless orphan, Grandmother used her niece, living under her care, as the scapegoat to separate the lovebirds.

“He seduced me,” Mother told me, in anger. “I didn’t even like him. He was too full of himself.”

Mother was seventeen when she got married under a judge’s order. Father was eight years older. Did Father resent being forced to marry a girl he did not love because of an unexpected pregnancy? Was that the source of his rage? As an adult, after their separation and divorce, I never discussed those early days living under his roof. I did not share such a close personal relationship with him. During her first return-visit to Guyana, after migrating to the United States, my younger sister asked him why he used to beat us so much.

“I didn’t want you-all to grow up bad,” he told her.

My only sister, the third-born child, was born a week after the British governor suspended the Guianese constitution and clandestinely landed British troops at dawn on October 9, 1953. From that day until our country’s independence in 1966, the presence of British soldiers on our streets and on parade became part of our daily lives.

“They were a bad influence on young girls,” Mother told me. She could tell lots of stories, she added, about the comings and goings of British Army officers at a house owned by a respectable woman in society. “You won’t believe the pretty young girls she had working for her.”

Young women vied for the attention of the single, young, white males from every new regiment of British soldiers that came to our shores on one-year tours of duty. They dreamed of marrying a white man and moving to the United Kingdom. Dozens of our local beauties succeeded, flying out with their army husbands at the end of their military posting.

Some men did not take kindly to the ‘limeys’ stealing their women. On the street where Father’s brother and his family lived, a soldier died during a street fight with a local black man over a woman. My uncle’s eldest son, then a teenager, was among the crowd that gathered to witness the fight. When the local police arrived, he was arrested and jailed along with other onlookers identified as inciting the squabble.

“When you see people fighting on the street, you go the other way,” Mother warned me and my siblings.

Though the adults often used a coded language for serious stuff we kids should not know about, it became clear to me that lots of violent men existed in the world. Men much worse than Father. Men who beat their wives to death. Men who slashed their wives and children with the cutlass or machete, like cane stalks on the sugar plantation (see captioned photo).

A local man killed a white female foreigner in the Promenade Gardens, an area we walked by on our way to and from elementary school. More warnings. The police found a missing girl’s body in an outdoor latrine pit. What had she done to deserve to die, to have her body dumped in a pit of human feces?

In my adolescent years, as for all young women, I became the target of idle young men liming on the sidewalks—with nothing better to do with their time than to hang around making remarks about female passers-by. Nothing escaped their scrutiny: your hair, face, breasts, hips, buttocks, legs, dresswear, the way you walked. Vulgarity was their preferred language. Depending on the location, I also faced the danger of being sexually assaulted.

The racial disturbances, during the 1960s struggle for independence, brought increased violence in our city streets and in villages along the coast and riverbanks. While protestors burned the commercial district on Black Friday, February 16, 1962, Mother and I huddled in the blackout around a transistor radio, listening to the news. We heard the British governor call for order in the streets. Father had left home earlier that day and had not yet returned. What a relief when he appeared around nine o’clock that evening! Exhausted and covered with soot, he gave us the terrible news. The building where his workplace was located had also burned to the ground. Father was now out of work. Six months went by before he found another job.

Photo Credit: Jolliffe Genealogy

The vileness of men intensified as the two major political parties battled to lead the colony to independence, pitting the majority blacks and East Indians against each other. Caught in the crossfire were the minority populations of Amerindians, Chinese, Portuguese, and people of mixed race, like our family. Political discussions between Father and his drinking buddies often grew heated. The newly formed Portuguese political party, led by a successful businessman, only divided them more. Taking sides came with risks to one’s safety. A group of young East Indian men once threatened to beat up Father for trying to protect his black friend.

As villages burned along the coast and families were attacked and killed, people were forced to flee their ancestral villages for refuge among people of their own kind. Two East Indian sisters joined our class at the Catholic high school for girls. With only the clothes on their backs, their family had fled the fire-bombing of their home in a coastal village. I saw only fear in their eyes. They never talked about what they had seen and experienced. Newspaper reports recounted all the killings, burnings, and defilement of women and girls. An eye for an eye. As a devout Catholic, I saw all this violence as the demons of Satan let loose among us. The demons possessing men showed no mercy for children.

I was thirteen when the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Works and Hydraulics and seven of his nine children, ranging from six to nineteen years old, were burnt to death in their home. The Permanent Secretary was an upstanding Catholic in the Portuguese community. That fatal night, as the family slept on the top floor, the arsonists saturated the interior stairway with gasoline, and then set it ablaze. The mother, badly burned, and her twenty-year-old daughter survived by jumping through a window on the top floor. On her return home from a show, their eldest daughter, twenty-four years old, could not contain her terror and grief as she looked on helplessly as her father and younger siblings perished in the flames. The perpetrators were never brought to justice.

Violent men have no regard for the children of our world.

I determined, then, never to get married and bring children into such a heartless and cruel world. That same year, I also began menstruating. “You’re a young lady now,” Mother told me. “Don’t let any boy touch you down there. He going give you a big belly.” She did not go into details. The threat of pregnancy was enough. No boy was going to get me pregnant and condemn me to a life of suffering, like my mother.

In biology class in high school, I learned all about the male and female genitalia and reproductive system. From more informed girls in class, I gained enlightenment not only about sexual intercourse, but also about sexual abuse within some families. Other girls my age faced much greater abuse than I did.

The hushed coded language among adults on my mother’s side of the family became clear to me. My own relatives were not immune. One of my older female cousins, raised by Grandfather, was a child of incest. On discovering her father’s identity as a young woman, I kept my distance from him. Another female cousin, also under Grandfather’s protection, was a bastard child—a curse in those days for an upright, Christian family. She was left behind in British Guiana when her teenage mother migrated to the United States.

By fifteen years old, I made up my mind to enter the convent, to devote my life to Jesus with whom I had developed a deep, spiritual connection. He filled me with courage to face my fears and insecurity to survive each new day. What better way to repay Him for all His blessings?

The day I left home for the convent, January 14, 1971, Father was next door at our landlord’s residence. Only my mother and sister attended the entrance ceremony held in the chapel of the Mother House of the religious order. Years later, the landlord told me that on that day, as he drowned his sorrow in alcohol, Father had blamed himself for my decision to become a nun.

“I was too hard on her,” Father had lamented. “I drive her away.”

During those years of a semi-cloistered life of self-denial, prayer, and reflection, I learned to forgive my father. I made my peace with him and with the abuse I had suffered under his care. As a nun in a patriarchal church, I saw more clearly the place of women in a world dominated by powerful men who use violence as a means of control. Not all men are violent or prone to violence. Not all women are nurturers.

My repressed rage erupted when I was a twenty-six-year-old nun struggling with sexual harassment in the workplace. The explosion of a firecracker, placed under my chair by a thirteen-year-old male student during a school party, brought the darkness deep within me into the light. My rage terrified me.

Regarded as inferior human beings—for we came from the rib of Adam, the Holy Bible claims—women have found myriad ways to survive and even thrive in a world where men have for millennia enjoyed privileges over the female body. In the following chapters, I share the stories of such women. Their names have been changed to protect their identity. These are stories from my viewpoint as a participant-observer, a term used by field researchers in anthropology and sociology.

That statistics is horrifying but not surprising. It is mostly the same all over the world. I am sorry to read that your father was so harsh and unkind. I started thinking about Dolores Clayborne. The violence you saw and experienced in Guyana was horrible. It is important to tell your stories.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Tom. I’m not familiar with Dolores Clayborne’s story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry Dolores Claiborne not Clayborne, a novel and movie by Stephen King. Her frequently drunk husband abused her and their daughter Selena. He was cruel when he was drunk. He dies in an accident and Dolores is accused of murder. She is not convicted because there is no evidence that she did it. However, the towns people believe otherwise and for 18 years they socially isolate her and harass her.

Then her elderly employer dies in another accident falling down the stairs and now she is accused again. This time it is more difficult for her because everyone is against her and are suspicious of her. Her daughter Selena, a journalist, comes back home to investigate. At first she is suspicious of her own mom until she realizes the situation and she begin to remember the dark memories from her childhood that she had repressed. She understands that her mother is a good person who was trapped in a horrible marriage, and that she tried everything to protect Selena, but she did not murder anyone. She does everything she can to help her mother and she is able to prove her case as well as expose the police chief who was trying to plant fake evidence against Dolores. Dolores had a horrible life but she was exonerated in the end.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks for the info, Tom. I’m not a Stephen King fan, so I was unaware of this novel.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t think any of those men had a right to be angry, it sounds like you had a tough life. Maybe guilt was behind that anger.

LikeLiked by 2 people

You may be right, Diana. Our men, too, have their own trauma growing up with violent fathers or mothers. One of my three brothers got the most severe beatings from my father. He mentioned recently that it took him years to reconcile with the abuse.

LikeLiked by 2 people

My answer to the chapter title question is that this is your story and should not be diluted by a more generalised theory – accurate as that may be. This is a terribly honest post revealing what has only been referred to briefly before. Don’t hold back because it makes most men like me uncomfortable.

LikeLiked by 5 people

Derrick, thanks very much for your comment on the chapter heading. My hope is that this work-in-progress will also generate engagement among our male population. Dismantling our violent patriarchal system of societal control and dominance will require collaboration of all genders worldwide.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Certainly

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think men anger because they see a bit of themselves in your writings. Thank you for your honesty.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for sharing your thoughts, Don. Male violence affects us all, regardless of our gender.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rosaliene, this is VERY sobering, powerful, and well-written truth-telling.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Thanks very much, Dave 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for writing this brave post, Rosaliene. I think the abuse statistics are similar in the U.S. I also believe patriarchy is a system of violence because of the power structure it creates. Those in power are always trying to maintain control, and the need to control others, to feel powerful, gets passed along. Unfortunately, in patriarchal systems, women are vulnerable and disposable. I agree that individual men are not violent; violent systems impose violence.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks for adding your voice, Madeline 🙂 As you point out, the U.S. is not immune from domestic and other forms of violence against women. The latest case making headlines about the Gilgo Beach serial killer comes to mind. What a shock for his unsuspecting wife and children!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I will never understand why some men need to be such A–holes. You can blame it on animal instinct, but animals use their rage and anger with better reason and precision. I believe it is passed down from generation to generation. My father was not violent and neither am I or my sons. Power, greed and control are the big motivating factors. We see it in a country’s politics and in interaction between unions and employers. Every one “fights” for their rights, as opposed to negotiating. They forget with rights, come responsibilities. Men need to feel uncomfortable of the actions of men. They need to think instead of simply acting.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks for sharing, Allan. I agree that “power, greed and control are the big motivating factors.” We see it playing out every day within the corridors of our government and corporate buildings.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dear Rosaliene, in its beginning this story, your life, is horrendous; it should not have been like that! However, looking back and seeing where you are now shows courage and a spirit that most never attain. Coming from a different a very settled background I don’t think I saw or even heard of violence against women, or men for that matter, until I was into my mid teens. Thank you for being so open and honest. 🌹🤗💐🙋♂️

LikeLiked by 3 people

Ashley, thanks for sharing your kind comments 🙂 Blessed are those among us whose lives have not been touched by violence ❤

LikeLike

Dear Rosaliene, your courage in the face of your upbringing inspires me. Thank you for sharing and not backing down.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much for your kind comments, Crystal. You, too, is a great inspiration for me ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your story is heartbreaking, Rosaliene, and reflects the human condition in a way that calls all of us, especially men, to look in the mirror. The complexity of the questions regarding violence — its origin and potential remedies — would take several books. We are not so different than we were when Thomas Hobbes, almost 400 years ago, wrote that the life of man in a state of nature was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Governments, he thought, could limit our innate tendency to do harm to others. Now the incivility even of elected officials leaves us and especially women, vulnerable. We must work to ensure that a woman’s body is hers to control, not a plaything of men in power.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Dr. Stein, thanks for mentioning the work of British political philosopher, Thomas Hobbes. It’s a reminder that the challenge we face today have been with us for centuries: How best to organize human society for the good of all? Evidence mounts that the power structure of Western civilization has failed the masses of humanity. Yet, we hold on to outdated ancient beliefs of our nature as human beings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Writing about this tough subject must be hard, especially because of the way you grew up. And while I found parts of the post difficult to read, I think you did an exceptional job of telling your story. The stories need to be heard and do not need to be softened because someone may think they’re too graphic. Great job!

LikeLiked by 4 people

Thanks very much, Mike and Kellye 🙂 It is, indeed, tough to write about the violence of the world in which we live. But it’s essential when telling the stories of women who have found a way to survive and sometimes triumph over all the obstacles placed in their path.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am so sorry this all happened to you (too).

Abuse comes in so many forms. Sexual abuse, physical abuse, and verbal abuse. Husbands suppressing their wives, parents abusing their children, employers molesting employees, and humans mistreating animals. So often a group of people believes they are superior to another race, religion, gender, or culture. A long endless list of suffering for too many.

As you know, I have been abused as a child, but “only” physically and verbally and I have scars -inside and outside. Nobody has ever heard my full story for many reasons. I don’t recall it all clearly and I don’t want to relive it. I was so young and later on, I decided that THIS part of my past would not define me. I made peace with my past, even sprinkled a bit of forgiveness, and work hard on helping others. I collect bras and feminine hygiene items for http://www.isupportthegirls.org, an organization that helps women in need. Homeless women and women in shelters. I stumbled into it and it opened my eyes. So much abuse and it got worse during the COVID lockdown. The shelters were full, and the stimulus money went to the abuser. Women in hiding don’t give up their new address.

I have seen and heard so much in my lifetime and it doesn’t end. Priests abusing children, and a neighbor who dug out a tulip bulb in her yard, because she had forgotten to buy onions and she was scared that her husband would get mad.

I will take my story with me into the cremation chamber. I am glad you share yours. May it heal you further!

LikeLiked by 4 people

My dad was a cop, and at the beginning of the pandemic, when bars and gyms were closed in Michigan, my heart went out to the families of police officers because there was no pause before cops got home from work and schools were closed so there was no escape from home for kids. I shuttered to think of what life was like inside those homes during those days.

LikeLiked by 5 people

The lockdown was a very tough time, indeed, Madeline.

LikeLike

Bridget, thanks for sharing your own experience with domestic violence. Our human societies are steeped in violence, most of it hidden in darkness, out of sight from public scrutiny. The abuser counts on the silence of the abused to perpetuate the violence.

Considering all the existential crises and threats we humans now face, the time has come for us to work together–male, female, and all genders–as equal partners to find a non-violent response to societal collapse.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Oh how much I wish we all would finally come together and fight abuse.

LikeLiked by 2 people

You are uniquely qualified to tell these important stories, (((((((dear Rosaliene))))))). Thank you. ❤️🙏

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you very much, Sunnyside ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are most welcome, Rosaliene. ❤️

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can understand where the anger came from. For years, holding that pain inside, telling ourselves to focus on the future and leave what happen in the past to stay there. But then new pain happens and it reminds us of the old pain and we can’t help ourselves but explode every little bit of what we had been holding behind what we thought was a strong protective wall for years. What a story you have to tell and that you survived through. And now you are helping other people tell their stories too. What a kind heart you have, helping others to release a little of that pain so that some day they don’t explode with rage as well…everyone has a breaking point. Thank you for sharing your story, I know that wasn’t easy. May God bless you always and keep you safe.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks very much for sharing and for your kind wishes ❤ As I will reveal when telling my mother's story in Chapter Three, our rage when unleased can have devastating effects on the lives of those closest and dearest to us. Over the years, I found ways to deal with my rage whenever it reared its head and, more recently, I'm using Zen mindfulness medication to release all its vestiges. Blessings ❤

LikeLike

This is an act of courage to relive those traumas and I applaud your efforts. Your writing is eloquent and powerful, and while it was difficult to read about all the pain and violence, I’m glad you’ve reconciled your past and found peace. As for the chapter heading, I hope you go with whatever feels right for YOU (rather than possibly self-censoring in anticipation of criticism).

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks very much for your kind words, Tracy ❤ Forgiveness and reconciliation are vital for attaining our inner peace.

I appreciate your feedback regarding the chapter heading. I'm guilty of self-censoring myself.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d guess we’re probably all guilty of self-censoring at one point or another. I know I am!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Men are the tools used to enforce control, greed, and in the case of Western governments, their white supremacists beliefs. But, as in the case of the black American Emmett Till, who was brutally lynched by a mob, it was at the instigation of a white woman and her false testimony. So, it’s systemic, in my opinion.

Humans are simply violent by nature. The Bible is our primer. We westerners worship a God whose solution to every difficult circumstances was the use of violence. Even the subjugation of the Promised Land was under the instruction that no living creature remain alive, innocent or not. How do you undo something so ingrained? Despite the same violence in other countries whose religion is not Abrahamic in origin, few justify their actions in the name of their God.

So, I think “Violence as Humanity’s Default System” Is a great title.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Pablo, thanks for the feedback on the chapter heading.

Violence is, indeed, systemic since it is built into the patriarchal system of human civilization. The god of the Old Testament is a male god of war. Violence begets violence. It affects us all, regardless of our gender, race, and social status.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s horrifying that there was and is and, I believe, always will be so much violence in the world. It’s part of human nature, in my opinion. And it’s perpetrated by males much more so than by females, as you note.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks for sharing your thoughts, Neil 🙂 Violence does appear to be part of our human nature, but, based on the behavior of other living species, I believe that it’s intended for self-defense and self/preservation. I do not believe it was intended to be used as the means of control over others.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Powerful, profound writing and a story that needs to be in sight and given a platform again and again. For many of us who were born into systematic violence and survived… the most damage is from the acceptance of society. Violence in all forms needs to be called out and addressed until it is no longer a part of any life.

You asked about your title for part two; “Violence as Humanity’s Default System.” — Violence is nonhuman or inhumane like an infection or illness— maybe instead of the word “Humanity’s” default, how about “ignorance’s” default?

Your powerful elegant writing allows the reader to continue with reading a painful subject and hopefully those readers will also become part of the solution. Incredible work Rosaliene! ☮️❤️🌷

LikeLiked by 3 people

Liza, thanks very much for your kind praise of my work! Thanks, too, for your feedback about the chapter heading.

I share your vision of a world without violence. You are so right when you say that our acceptance of violence is most damaging. Our incapacity as a nation to pass sensible gun laws to end mass shootings is a glaring example of this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are very welcome, and I hope the publication is expansive and productive!

….regarding the gun laws, sadly, the only thing I can decipher is the ignorance, fear, and willful greed. Maybe soon, enough will be enough.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, this hits hard and deep. These are some of the terrible truths we live with. Your writing is open and vulnerable. This will be a difficult book both to write and to read, but hopefully it will be used for good.

My own father was a pacifist, after what he had experienced in the German slave labor camps, and it was my mother who was the violent one. He was the first man in Quebec to be granted a divorce on the grounds of mental and physical cruelty.

Violence has bred domestic violence and so many suffer because of it. These are difficult topics to read about or to discuss, but when people see themselves in the pages, and see how others have overcome their situations, it gives hope they too can overcome their own situation.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Tamara, I’m hoping that the stories of the women (to be) featured in the book will be interesting and inspiring.

Sorry to hear about your violent mother. Depending upon their own trauma and experience with abuse, our mothers can be quite cold, cruel, and abusive. I was not here in the USA when my mother’s rage erupted. During the years I lived apart from my family, each of my siblings had to face her wrath. Then came my turn.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Sorry to hear that. Yes, rage from either parent is terrifying and terrible for a child to go through, and you’re very right in saying that their own experiences can lead to them having rage. I’m writing about those things in my new book. Difficult to go back and remember those things to be able to write about it. I’m hoping you’re balancing your writing with self care breaks to relieve the stress and anxiety it brings up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tamara, I believe that you and I are both strong enough to embark on the journey of re-living/re-examining our past dark experiences. Since the focus of my work-in-progress is telling the stories of other women, I’ve become less judgemental of other women, even those whose beliefs and choices differ/clash with mine.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, that’s an amazing positive to have come to. Yes, we’re both at good points to be able to take on our projects. We each have responsibilities to tell the stories in the most honorable way possible to do justice to our subjects.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I like the title. Also “men” or “man” can refer to either sex .

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for the feedback, John 🙂

LikeLike

You show a great deal of courage to be so honest about so many horrible events and about how dreadful some men can be. It will take a long time to turn the tide, though, as so many reports on the British Police Forces, for example, have shown recently.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks very much, John 🙂 I know it will take a long time for there to be real change.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great blog about a very tough subject. You are a strong woman and a great inspiration in sharing what you went through.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much for your kind words, Vinny ❤

LikeLike

Rosaliene! I am blown away by your stories! The way you have written this has be freeing to you. So well put, I felt and can picture every word.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Belladonna!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’ve really seen it all Rosaline, sorry about your father’s ill-treatment, these things have long-lasting effects on kids unfortunately. Kids blame themselves for sins they haven’t committed. True, everyone has a story to tell!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Zet Ar ❤ I'm working right now on forgiving my teenage-self.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a pleasure, take care!

LikeLiked by 1 person

As a reader, this is a lot for me to process. Then I think, but you, Rosaliene LIVED through it! Much of what you described sounds like hell to me. To be honest, I don’t like the chapter title, “Violence as Humanity’s Default System.” I guess it’s because I don’t believe violence is the default for humanity as a whole. Maybe “The Violence of Man” or something about Suffering the Violence of Man. Maybe there’s another title for that chapter. I don’t know. Realizing what your witnessed and lived through, maybe violence was the default of men in your experience. I suppose I’ve been sheltered, having never experienced any real physical violence. On the other hand, the way you describe your father reminds me of the things my husband has told me about his father. He did not beat my mother-in-law, but he did beat my husband (the oldest) and the second oldest son, badly, was verbally abusive, narcissistic, and he did not give them enough money to live on. It seems like he told one of them later something similar to what your father said as to the reason – about not wanting them to be bad. How bizarre and horrible not to know any other ways to instill goodness. For him and your father, violence was the default. Thank you for your courage, Rosaliene. Your writing is powerful and important. We need to know these uncomfortable truths. I look forward to reading about how women survive and go on in to thrive is spite of violence.

LikeLiked by 2 people

JoAnna, as I alerted, this is a very uncomfortable subject. What I experienced in my youth (1950s-1970s) was nothing compared to the violence African Americans faced under Jim Crow laws (1877-1954), non-white South Africans under Apartheid (1948-1994), and the Vietnamese during the Vietnam War (1945-1975). War is the ultimate form of violence against humanity and we, as a nation, are not innocent when it comes to creating hell on Earth for families in distant lands.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reminding me of this reality. All these atrocities are important to learn about and remember.

LikeLiked by 1 person

JoAnna, I don’t enjoy bringing up these uncomfortable subjects. However, if we humans of all genders and skin-color are to come together to deal with the existential crises we now face as a species, we must acknowledge what is keeping us apart.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Indeed. Thank you for this insight.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What to say?

In my case I was lucky, with a family with little aggressiveness and family violence, of course my parents had arguments, but my father never raised his hand to hit my mother, He was always chivalrous, as a child violence existed in the street and at school, with rowdy classmates, with the occasional fight with one of my brothers, but childish things, as older adolescents, did not happen.

I think that violence is suffered and then executed by the same person who received the abuse and his soul it’s filled with anger, and then, since he has the strength and opportunity to exercise violence, he does so, thus forming a cycle of violence perpetrated by such individuals and received by the weakest, and defenseless.

As an anecdote a couple of years ago I was the neighbor of a newly married couple, where but daily, I first heard arguments and then violence, and to be honest the one that started, the arguments was the woman, and the arguments rose in tone, while the The man asked her to stop, but she got angrier, and the man finally assaulted her.

Many times I was tempted to call the police, but I know that none of the neighbors around did it, because it is well known, that after doing that, the couple takes it against the one who denounced them!

And here we have a saying: In fights between husband and wife, do not get involved, stay out! Because, later, the couple will take it against you!

😯🤷♂️

LikeLiked by 3 people

Burning Heart, thanks for reading and adding your comments 🙂 You were fortunate not to have been touched by the violence of our world.

It’s true that getting involved in fights between husband and wife can result in a backlash. From what I observe among cases of domestic violence among middle-class Americans that end in homicide, the control and violence are done within strict privacy, taking unsuspecting neighbors by surprise.

LikeLike

It is quite by accident that I am here viewing your intense

post Rosaline but I have to admit that I am happy I did.

After all you made clear how horrible life was decades ago

and probably still very much remains in countries I know little

to nothing about. Thank you for bringing this out into the open

where more people can have a look at these deplorable conditions. hugs, Eddie

LikeLiked by 3 people

Eddie Two Hawks, thanks for dropping by and sharing your thoughts ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re very welcome Rosaliene

LikeLiked by 1 person

WOW Rosaliene, this was indeed a tough topic to discuss. It’s horrifying, but so true how much our surroundings, especially growing up, can affect us and our relationships as we become adults. This statistics that you posted are alarming and horrifying. Thanks so much for addressing such a tough topic my friend. 🙏🏼💖🙏🏼

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much for reading, Kym. It’s so much easier to address these tough topics in works of fiction where I’m able to distance myself from the characters. As Katharine Otto noted in her comment: I’ve moved on. I am ready to tell our stories ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

There you go Rosaliene. 💖 I am so there with you my dear friend! I get it! 🤗🙏🏼😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a saga! But you have moved on . . . Now you have sons . . .

LikeLiked by 2 people

Katharine, I have indeed moved on. I thank the gods…no girl child.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Understood . . .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing!!.. sorry that you and others had to experience and deal with things of this nature… with your courage to speak out, the world is learning more about itself and enabling others to gather courage and work together to help make this world a better place… just keep your fingers doing the walking and your heart doing the talking and you will make a difference for many!!.. 🙂

Hope all is well in your part of the universe and until we meet again…

May your day be touched

by a bit of Irish luck,

Brightened by a song

in your heart,

And warmed by the smiles

of people you love.

(Irish Saying)

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dutch, thanks very much for your kind words ❤

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing your truth Rosaliene, it is sobering and very thought provoking. There are really no excuses for violence perpetuated against those who are the most vulnerable, and are not able to defend themselves.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Zumayo 🙂 Your thoughts are much appreciated.

LikeLike