Tags

British Guiana (Guyana)/South America, Creative writing mojo, Dutch legacy/Guyana, Kill your darlings, Setting the stage for a book, Severed ancestral roots, Slavery and Colonialism

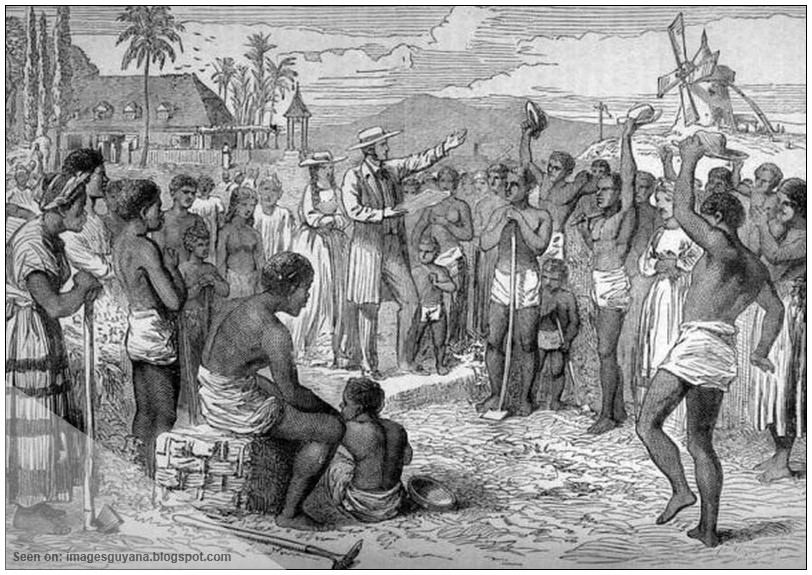

Photo Credit: Images Guyana Blogspot

On Monday, May 22nd, I revisited Chapter One of my two-year-long neglected work in progress. As I revised the chapter, the familiar thrill of creating images with words surprised me. Once again, I was eager to engage with the creative process. I woke up in the mornings with ideas for improving or adding to the text. What a joy!

Since last working on this chapter in January 2020, I found it easier to “kill [my] darlings”—words, phrases, sentences, and even entire paragraphs. While maintaining the purpose of setting the stage of the world in which the featured women fought for agency in their lives, I found it challenging to cut and tighten critical historical information. Although the players in our own time have changed somewhat, women and minority groups are still fighting the same battles.

To establish the author as a participant-observer in the lives of these women, the narrative also contains autobiographical information. The author, like all the players on the stage, shares their legacy of severed ancestral roots.

Regardless of the efforts of some among us to rewrite or erase America’s brutal history, the legacies of slavery and colonialism continue to impact our lives at home and worldwide.

WOMEN WITH AGENCY

(Working Title)

Chapter One: Severed Roots

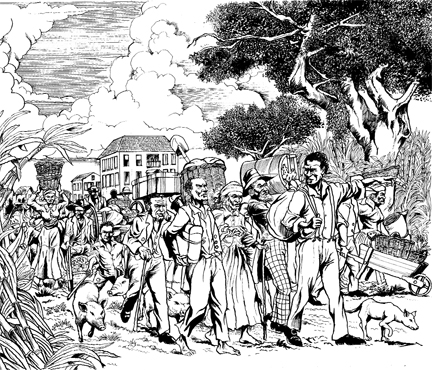

Photo Credit: Cumberland Scarrow

When I took my first breath on leaving my mother’s womb, I did not know the adverse conditions already stacked up against my chances for survival. Born female. My mother, just turned eighteen years, trapped in an undesirable marriage. My father, eight years older, forced to wed the minor he had seduced and impregnated. A poor, working-class family in a small backwater country, then known as British Guiana, forged by violence. Subjects of Empire forgotten by the gods. Brown-skinned in a region dominated by the white man, where skin color defined one’s place in society.

That year I made my entrance, bawling at the stark sensations of a strange new world, political upheavals across the waning British Empire were already in motion. King George VI, the reigning British monarch since 1936 and the first Head of the British Commonwealth, died on June 2, 1953. Our new monarch was a woman, crowned Queen Elizabeth II. Just twenty-five years old. God save the Queen. Long may she reign. My mother was twenty years; my father twenty-eight years.

As I grew older and became aware of the world around me, I observed that life under the British colonial government was no paradise for descendants of peoples transported to this conquered territory, first settled by indigenous peoples over thirteen thousand years ago. Thrown together for the capital gains of the then lucrative European sugar market, we owed our existence mainly to sugar cane cultivation. The wounds of discord and resentment between the diverse ethnic populations ran deep.

After Christopher Columbus first stumbled on the so-called New World in 1492, under the auspices of the Spanish Crown, Dutch traders were the first to claim the territory located on the northern shoulder of what later became known as South America. Despite continual Spanish aggression, by 1648, the Dutch managed to establish three colonies—Essequibo, Berbice, and later Demerara—built on the backs of African slaves, first introduced in 1633.

After two failed attempts in the late 1700s to grab the colonies from Dutch settlers, the British finally gained a foothold on the vast continent dominated by Spain and Portugal. In 1831, during the reign of King William IV (1830-1837), Holland’s three colonies became British Guiana. After 232 years, English replaced Dutch as the official language. Hundreds of Dutch words in common use, such as koker (sluice) and stelling (pier), became part of the Guianese English language. The names of villages are also a reminder of Holland’s enduring influence on the colony: Beterverwagting, Meerzorg, Uitvlugt, and Vergenoegen are just a few examples.

The greatest Dutch legacy is the transformation of the coastal landscape from swampland into agricultural land for cotton and sugar cane cultivation. The Dutch engineering marvel of forty-nine miles of drainage canals and ditches, as well as sixteen miles of waterways for transportation and irrigation on higher ground was made possible with African slave labor. In 1948, the British Venn Sugar Commission estimated that the original Dutch construction of these waterways must have entailed moving at least one hundred million tons of soil. What a muddy hellscape for the slave laborers that must have been!

Artist’s Impression by Barrington Braithwaite

Photo Credit: Stabroek News, Guyana

Decades of intermittent rebellions for freedom gained traction when King William IV, pressured by the abolitionists, passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833, abolishing slavery throughout the British Empire. The new law did not take effect in Guiana until August 1, 1834. Jubilation was short-lived for the estimated 69,579 slaves on learning that they faced a six-year transition period as apprenticed laborers. Same punishing conditions. Same demanding bosses. Four years of open revolt and constant opposition short-circuited the new apprenticeship system.

After more than two hundred years of African enslavement of mind and body, the darkness of oppression lifted from across the land. Freed at last, the blacks fled the inhumane conditions of plantation life. Over time they would learn that laws do not automatically change human attitudes and behavior towards others we deem as inferior beings.

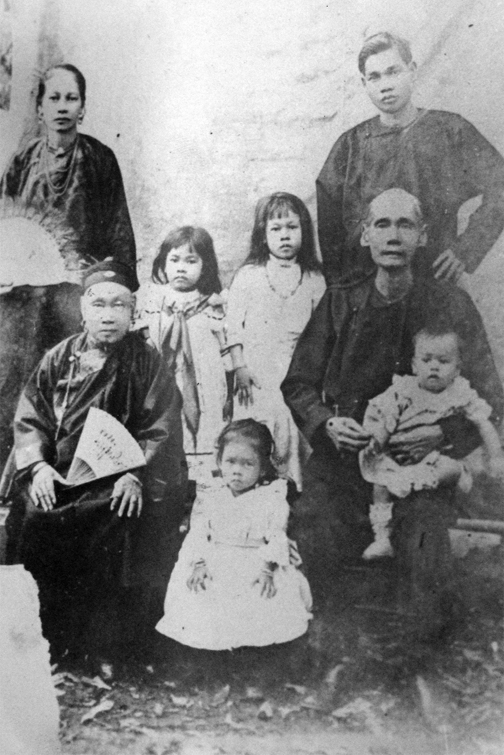

Photo Credit: Guyanese Portuguese Facebook Group

Faced with a dire labor shortage, the white planter class first looked to Portugal for help. After a 78-day voyage via London on the Louisa Baillie, forty-eight peasant farmers from the Portuguese colony of Madeira arrived on May 3, 1835. Though they were hard workers with experience of sugar cane cultivation, they suffered many casualties under the deplorable living conditions on Guiana’s plantations. Owing to the harsh economic conditions and political unrest in Madeira at the time, Madeirans continued coming to Guiana. They ventured into the husker and retail trade, coming into direct conflict with ex-slaves who operated in the trade. By 1882, when migration ended, there were 30,645 Portuguese from Madeira as well as the Azores and Cape Verdes who had settled in the colony. Though the white colonial government did not classify them as “white” but rather as “Portuguese,” they enjoyed a high social status just below the British plantocracy.

Source Credit: iNews Guyana (Photo from Houghton Library, Harvard University)

British India soon provided a new prospect for a steady, cheap labor supply. The East Indians or “coolies,” as they were called, proved more successful for the rigors of plantation life. Contracted for a five-year period as indentured laborers—instituting another form of slavery—the first group of 396 East Indians arrived on May 5, 1838, from India on the Whitby and Hesperus. Eighteen Indians died during the 112-day voyage. By the end of the Indian Indentureship system in April 1917, 238,979 East Indian immigrants had set foot on the shores of Guiana. Like the former black slaves, their dark skin placed them on the lower rungs of British colonial society.

Photo Credit: Stabroek News, Guyana

The white planter class also experimented with indentured laborers from China. In early 1853, three ships arrived in the colony, carrying 647 Chinese immigrants. Over the following twenty-six years, ending in 1879, more than 13,000 Chinese came to Guiana, forming the nucleus of the minority Chinese community in the colony.

Whose blood pumps through my arteries? I know very little. My maternal grandparents migrated to the United States in the 1940s, leaving behind my mother and her two youngest female siblings in British Guiana under the care of their mother’s sister. Grandmother, as we called her, died when I was about three or four years old. She was married to a soft spoken and generous man we called Grandfather. A colored man, over six-foot-five tall, he owned and operated a bakery in the capital, Georgetown. As kids, my four siblings and I spent many happy times with our cousins at Grandfather’s large and spacious home above the bakery and shop. A wisp of baking bread evokes memories of those carefree days.

My maternal grandmother was born in British Guiana to Portuguese immigrants from Portugal (father) and Bolivia (mother). She married a black man, a descendant of African slaves, born in the British West Indian Island of Barbados. He operated an import-export business between the two British colonies. Since they migrated to the United States almost a decade before my conception, I never had the chance to meet them and hear their stories. My mother never spoke about them. As children, we knew very few of our Portuguese relatives. Moreover, we had no connection with our black, Barbadian relatives.

My paternal grandparents, who had died when my father was an adolescent, also remain a mystery. I have learned only that my Chinese paternal grandfather arrived in British Guiana as a six-year-old from China. Where in China? Which year and vessel did he arrive in the colony? I know only that, after his death, his common law wife or mistress and their four sons—a fifth son died from drowning—inherited none of his wealth or property. My father had frequent contact with only one Chinese relative whose son, a few years older than I am, often visited our home.

My paternal grandmother’s origin is lost in humanity’s harsh realities. Based on her surname, she was a colored woman with Scottish ancestry. Was she a bastard child of a white rapist? Following her death, her orphaned sons were separated: two were raised by a relative and the other two by a close friend. My father, too, never talked about his past nor his parents.

What secrets and hurts did my mother and father harbor? In dealing with my own emotional wounds, I have come to understand the pain of remembering and verbalizing our trauma. As I would learn when I reunited with my mother in Los Angeles, after over thirty years of separation, my parents were two broken individuals thrown together in an unholy matrimony.

In growing up in a multiracial and multi-ethnic society, severed from its ancestral roots, I learned to embrace others with all their differences. Beginning with the false conception of male superiority over the female, our differences are social constructions to keep the masses of humanity divided. So much easier for the (heterosexual or cisgender) male minority power elite to control us. Since the creation of the patriarchy over four thousand years ago, violence has remained their preferred strategy for deterring and eliminating all threats to their dominance.

It certainly looks as if it is. Even if this wasn’t about you it would be enthralling

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Derrick!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article and photos! I used to collect related photos and prints. They can tell a lot…

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Friedrich! Photos do tell a lot. The same can be said for great paintings.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This is extremely well written and interesting history and biography. I am sorry you had a difficult start in life.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Thomas 🙂 Adversity is a part of our lives that can make us grow stronger and more resilient.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Very interesting, if not heartbreaking, stories of your family history. I really don’t know much about British Guiana history, but can see how much destruction colonists caused to people’s lives, for their own own gain. Thanks for sharing this Rosaliene, Maggie

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks very much, Maggie 🙂 The history of each country, regardless of its size, has a lot to teach us about the human destructive forces that forge our individual and collective lives.

LikeLike

Congratulations, Rosaliene, on the return to your book! The chapter you posted is a compelling, sobering combination of “the personal and the political” (history, social commentary, etc.).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Dave! For better or worse, we’ve come to compartmentalize all aspects of our lives, when, in fact, everything is connected.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderfully written and I am glad you got your mojo back.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Bridget!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is striking to read so thorough a history within the blogging world, both personal and objective, of a place unknown to most of us. I’m glad the muse has found you again, Rosaliene. We are all better for it.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks very much, Dr. Stein 🙂 I’m pleased to know that the historical content doesn’t bog down the narrative–a criticism the first draft received from a member of our now defunct writers’ critique group.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent post, Rosaliene, and first chapter of your family history in Guiana and the complex effects of colonialism. Congratulations on returning to your work.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Barbara! So glad you like my first chapter. I plan to revise Chapter Two, “The Violence of Men,” next week.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Rosaliene,

This chapter of you, your family, and your cultural history shows something of the open-minded and compassionate person you are today. True there has been lots of suffering. Otherwise, where would the stories come from?

You refer to happy childhood memories above your grandfather’s bakery, so you have also experienced the alternative. This deepens your soul’s understanding of the infinite complexities of all our lives. I look forward to reading more.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks very much, Katharine, for sharing your insightful perspective 🙂 Adversity can either break or strengthen us. The women in my life showed me the way to endure and triumph.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You tell a good tale Rosaliene. The colonizers always think they are doing what is best for the land and people, but they are really only doing what is best for them. Have a good Sunday. Allan

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Allan 🙂 I was hoping to get outdoors today for gardening but a marine layer refuses to budge 😦

LikeLiked by 1 person

Is this fiction or nonfiction? And good for you to get back to work. “I’m painting the house” is my current excuse but I have at least gotten back into it a bit and have two more days of my part of the job. I don’t think history should be erased or rewritten by anyone. Which includes changing literature–all of which reflects the attitudes of the times–I shudder to think of someone rewriting my work. Women still have it the worst, of course. Good luck with it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Lynn, it’s a work of creative non-fiction. Your question suggests that I’ve succeeded in setting the “creative tone” from the get-go. I appreciate your good wishes 🙂

Excuses sometimes hide the real cause for our writer’s block. While working on my first novel, I got stuck for a month when faced with an emotionally charged scene that stirred up painful memories of the break-up of my marriage. I found a way to use the pain to carry me through.

This time was similar, but much worse. I thought that I could get beyond my blockage on writing about Brazil by focusing only on the women to be featured. Still, it entailed reliving the trauma of raising my sons alone in Brazil. My mother’s mental health decline and our estranged relationship added to my emotional overload.

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing your history; your family’s and your country’s. Wealth of the few built on the misery of the many. All that dirt moved by hand!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Rebecca, I appreciate your interest in knowing more about our story 🙂 The trauma of colonialism and slavery is still perpetuated today through our capitalist globalized economic system and the institutions created to support the system.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, subsistence wages abound where our companies have outsourced abroad.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I rejoice the return of your mojo and look forward to reading more. Telling these hard stories is essential, but trauma based memories can exact a high price, as you know so well. Be kind to yourself, dear one. ❤️❤️❤️🙏

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Sunnyside 🙂 Being kind to myself is still a work in progress after years of spiritual training to put the needs of others before my own ❤

LikeLiked by 2 people

❤️❤️❤️🙏

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a fascinating story of endurance and courage. Sometimes, we need to walk away from our writing for a clearer perspective. Your writing is insightful and keeps the reader engaged in your very intricate and deep background.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much for your positive comments, Mary 🙂 It’s always good to know when one is headed in the right direction.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Chapter one is powerful. It’s great that you have returned to writing the book you had set aside.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks very much, Neil 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Maybe you were meant to descend from ancestors of different cultural diversity so that you are able to embrace their differences and to value all their cultures.

Although different races to Him who created them, could have been made to resemble a bouquet of flowers, dark-skinned people are regarded as 2nd class citizens in this world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Zet Ar, thanks for adding your voice from South Africa. I remain hopeful that my stories will open the eyes of white members of our human family to the reality of the lives of dark-skinned people, not only in the USA but also worldwide. Such is the lasting legacy of European colonialism and the triumph of capitalism.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rosaliene, what a great bit of writing. It immediately brought up anger in Tubularsock. (True —- easy to do.) This period of time in history always brings Tubularsock to his boiling point.

Very interesting material to work with and so many directions on the horizon of possibility.

Though you don’t need advice but that never stopped Tubularsock, Tubularsock’s working title wouldn’t be WOMEN WITH AGENCY. Tubularsock’s working title would be KICK ASS WOMEN MAKE THEIR MOVE!

Wishing you well with your endeavor and keep it real!

Peace.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Tubularsock. It’s not my intention to anger readers, but to open minds and hearts to different realities of life.

I’m sorry to disappoint you, but the women portrayed in my book were/are not “kick ass” women in the sense of “act[ing] in a forceful or aggressive manner” (definition from an online dictionary).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Could I ask you, which South/Central American colony do you think has benefited from the nation which colonised it? (If any).

I’m still watching Simon Reeve and really, in the first four episodes, the answer would be “None of the above”, which does not really reflect what seems to have happened in Africa where many ex-British colonies have done better than those of, say, Portugal or France.

I enjoyed your description of contemporary America, by the way: “Regardless of the efforts of some among us to rewrite or erase America’s brutal history, the legacies of slavery and colonialism continue to impact our lives at home and worldwide.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

John, the sole purpose of the European colonizer was to extract the natural resources, using the cheapest labor available, for the economic gain of the European power. I cannot speak for the countries of the African continent.

Reflecting on the role of the West Indian economy in Britain’s economic development, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1940-45, 1951-55) stated:

“Our possession of the West Indies . . . gave us the strength, the support, but especially the capital, the wealth, at a time when no other European nation possessed such a reserve, which enabled us to come through the great struggles of the Napoleonic Wars, the keen competition of commerce in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and enabled us not only to acquire the appendages of possessions which we have, but also to lay the foundation of that commercial and financial leadership which, when the world was young, when everything outside of Europe was underdeveloped, enabled us to make our great position in the world.”

As quoted in: How BRITAIN Underdeveloped the CARIBBEAN: A Reparation Response to Europe’s Legacy of Plunder and Poverty by Hilary McD. Beckles, published by The University of the West Indies Press, Jamaica, 2021 (p. 7).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much for that comprehensive reply. One other thing that I remember from a different Simon Reeve series was that Belize was doing well in Central America, in contrast to the other little countries in that area.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s good news, John.

LikeLike

Beautifully told Rosalienne, there is nothing better than the creative fire, keep it burning, I’m so happy that you are inspired.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Kate! Here’s hoping that the creative fire keeps burning 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing a part of your world!!.. hopefully with today’s knowledge and technology we can learn more about each other and have a better understanding and create better peaceful world… keep your fingers doing the walking and your heart doing the talking!!.. 🙂

Hope your path is paved with dreams and until we meet again..

May your day be touched

by a bit of Irish luck,

Brightened by a song

in your heart,

And warmed by the smiles

of people you love.

(Irish Saying)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Dutch 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing your family history and how it’s been by the complexity of colonization. It seems like some reflective time has done you a lot of good. As they say in the movie Sully, “A delay is better than a disaster”. I’m certainly adopting that philosophy of late

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Claire. Colonization has shaped the world that we live in today. I’ve found that the practice of mindfulness has given me a clearer focus.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m delighted that you have rediscovered your writing muse again! Bravo!

I’ll admit I became a little bogged down after “After Christopher Columbus first stumbled…” but when you picked up your personal narrative, I understood what groundwork you were laying.

As a reader, I’d have liked to see little bits and pieces of your family history sprinkled into the historical paragraphs. Your story and your family history is powerful, so please don’t be shy in adding more in!

Too many right-leaning people are denying the existence of racism today, they feel more comfortable seeing it in the past, not in the present time, for that would mean admitting to themselves that Meemaw and Pawpaw, or their Mon and Dad themselves did and said some pretty awful things.

Write your story, and liberally add yourself and your family to the narrative, for that is what makes it personal and helps people to gain perspective!

Don’t hold back! Let your experiences and emotions show in the words, you do not need to withhold!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tamara, thanks for the feedback on Chapter One of my work in progress. What I know about my family history, both maternal and paternal, I have shared in Chapter One. My own story will unfold in the chapters ahead as I share the stories of the women in my life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I see the conundrum!

Nonetheless, I’m delighted that you are writing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Since the creation of the patriarchy over four thousand Bb years ago, violence has remained their preferred strategy for deterring and eliminating all threats to their dominance.”

Your words reveal a dismal truth that has been perpetuated by governments and religions of the world for these 4,000 years—domination through violence.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Pablo. It’s good to know that I’m not the only one who understands this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yup. I’ve studied Eastern religions. The Buddha had to be taught by his mother-in-law that women deserved a role in the monastic life. He changed his teachings to accommodate, not her, but the principle.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By the way Rosaliene, which of the two of your novels would you recommend before the other?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pablo, I would recommend “Under the Tamarind Tree.” Though the stories stand alone, they are set during different time periods in Guyana’s history: Under the Tamarind Tree during 1950-1970 and The Twisted Circle during 1979-1980. You can learn more about each novel at my Author Website (see links below).

I appreciate your interest 🙂

https://www.rosalienebacchus.com/novel-under-the-tamarind-tree.html

https://www.rosalienebacchus.com/novel-the-twisted-circle.html

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. I usually don’t read fiction, but I gather your stories may contain more truth than fiction.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is great news, Pablo! There are several truths about the human condition in “Under the Tamarind Tree.” Above all, though, I hope that you find the story an enjoyable read 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

By the way, I had read your Author Websites earlier and found each story intriguing in its own right. I just wasn’t sure which one would be the most interesting of the two stories.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good to know.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rosaliene. I’m so happy you are back at writing!! I see why you needed a mental break, you dig deep into history and this isn’t easy. Kudos to you!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, Belladonna!

LikeLiked by 1 person

💖

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mixed feelings about your post: so glad you wrote it, and it whets my appetites for your book; and so sad to hear about your family story – as it is the story of so many taken in used- abused. Thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rusty, thanks very much for reading and sharing your thoughts ❤

LikeLike