Tags

Amnesty for illegal immigrants in Brazil, Brazilian ID Cards for foreigners, Brazilian Immigration Authorities (DPMAF), Certidão de Antecedentes Criminais, Declaração de Bom Procedimento, Departamento de Polícia Federal (DPF), Illegal immigrants, Permanent residence in Brazil, Registro Provisório

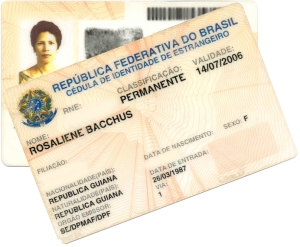

Brazilian ID Card for Foreigners with Permanent Status / Brazil’s Cédula de Identidade de Estrangeiro

Brazilian ID Card for Foreigners with Permanent Status / Brazil’s Cédula de Identidade de Estrangeiro

Nineteen months after our arrival in Brazil, President José Sarney signed a Decree-Law permitting all illegal immigrants (estimated at about 500,000) to regularize their situation with the Departamento de Polícia Federal (DPF). Miracles do happen.

Uneasiness clung to me the afternoon I accompanied my husband and two sons to the Federal Police Department in Fortaleza, capital of Ceará. Would we be deported? My husband led the way through the checkpoint at the entrance and onwards to the sector indicated.

We were not the only foreigners seeking amnesty at the four-foot high counter. The Federal Police Officer who attended to us was soft-spoken and cordial. We presented our Guyanese passports with Brazilian Entry Stamps, showing location and date of entry. While we completed the Provisional Registration Forms, our restless four and six-year-old sons disappeared behind a door at one end of the waiting area. An officer appeared with them. His smile put me at ease.

Later, armed with my Protocol from the DPF – valid for 180 days, awaiting a Registro Provisório (Provisional Register) – I went in search of a job. As mentioned in an earlier post (Brazilian Friend of the Heart, 16 Oct 2011), I obtained a secretarial position at a private school offering courses in British English and culture.

Our Registro Provisório was valid for two years. During that period, I worked at an import-export consultancy firm. When the DPF initiated our application process for permanent resident status, they renewed our Provisional Register for another two years. After paying our processing fees, we set about obtaining the necessary medical tests and documents required for submission to the Brazilian Immigration Authorities (DPMAF – Delegacia de Polícia Marítima, Aerea e de Fronteiras).

Medical tests covered vision, auditory, lungs, heart, blood, urine, and stool. My handwritten Declaração de Bom Procedimento (Declaration of Good Conduct) outlined my place of residence, job title and functions, name and location of sons’ school, and my reasons for seeking permanent residence in Brazil. My employer also had to provide a declaration of my employment status with his firm. The Guyana Embassy in Brasília confirmed that we had no criminal record.

Obtaining the Certidão de Antecedentes Criminais (Certificate of Criminal Records), took us to an unsavory place. Some of the people waiting in line increased my wariness. Our interrogation, in separate rooms, caused me even more concern for our safety. Although I was not mistreated, I felt like a crime suspect. What a relief when we left with our CACs, certifying “non-existence of criminal record”!

At some point, at the Federal Police Department, a female official took our complete fingerprints from both hands. My sons had fun removing the ink from their fingertips with a bright pink, grainy paste. In another office, a photographer took head shots for DPF records and our ID cards.

When my sons and I received our Brazilian ID Cards for Foreigners in 1994, I was managing the import/export operations of a large melon producer and exporter.

That process must have kept you on tenterhooks. I mean, it was great they offered that, but until it was official in 1994, I bet it was always there in the back of your mind.

LikeLike

You’re right, Rachel. It did keep me on tenterhooks, especially since my husband left Brazil in 1991. I had to prove to the Brazilian Immigration Authorities that I could earn enough to support myself and sons. Getting that position at the melon producer made a great difference.

LikeLike

Good description, Rose.

A question: was your status in Brazil actually “illegal” (you had a stamped passport, right?) or was it not permanent? I don’t quite understand.

LikeLike

Thanks for dropping by, Angela.

We entered Brazil legally with visitor’s visas. Our passports were stamped at our point of entry – Boa Vista, capital of the state of Roraima, near Guyana’s southern border with Brazil.

To Brazilian immigration authorities, we were “foreigners with irregular situation.”

LikeLike

Every country, apparently, has its own rules and terms – certainly doesn’t make things easier.

The process of emigration has always seemed overwhelming to me. While I can understand the motivations – from financial to adventuresome, for example – it’s always seemed to me to take an enormous amount of courage.

LikeLike

It does take “an enormous amount of courage,” Angela. And even more courage to start a new life.

LikeLike

do they still give amnesty?and if yes how can it be obtained

LikeLike

Seth, thanks for reading my article.

You can obtain up-to-date information about amnesty in Brazil through the Associação Nacional de Estrangeiros e Imigrantes no Brasil (ANEIB). They have a Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/estrangeiros.aneib. If you are not a Facebook user, you will have to open an account to access their page. I was unable to find any website in their name.

LikeLike

My Brasilian permanent visa expired.I completed the forms for my renewal.I am

waiting for my new permanent visa to arrive in November 2014.

LikeLike

Percy, I hope your new Brazilian permanent visa arrives soon.

All the best.

LikeLike

Rosaliene, my Brazilian Permanent Visa Card expires on Nov. 21, 2015. I will turn 60 this month of October on the 17th. After reading different blogs on other sites, I read that if you turn 60 before the expiration date on your card, you have nothing to worry about. I’d be more at ease if I could find out if this is actually true or if I have to renew my card. Can you tell me? If this is true, do I need to renew my card in the future or is it permitted to continue to use the one I have?

Thanks so much in advance, Mary Lou Borchert

LikeLike

Mary Lou, I no longer live in Brazil so I cannot advise you on this matter. If you live outside of Brazil, I suggest that you contact the Brazilian Consulate or Embassy nearest to you. If you are residing in Brazil, you’ll have to contact the Brazilian Federal Police Department.

LikeLike

Thank you for replying! I will contact the embassy. Take care!

LikeLike

You’re welcome, Mary Lou. Hope it works out well for you.

LikeLike